Editor's Note: Thanks to Sue Reaney for this scan.

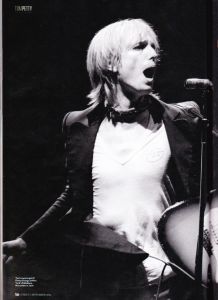

"I'm Not Mr. Laidback!"

By Jason Anderson

Uncut - September 2014

"I did go through a lot of my life with a short fuse, where I could erupt into a serious rage..." At home on his Malibu estate, TOM PETTY is reflecting on his temper, his tempestous career with the Heartbreakers, and his urgent and essential new album, Hypnotic Eye. Petty might be calmer these days, but there are still clearly battles to be fought. "I can't save the world," he says, "I can only bitch about it!"

The troubles of the world seem a long way away from the home studio at Tom Petty's Malibu estate. The singer's favourite spot on the property, it lies at the furthest end of his spread, which consists of a long, connected set of red-roofed ranch houses. Modest by the neighbourhood's standards, the most eye-catching features near the main house are a small fountain and an oval-shaped pool that's hardly what you'd call Olympic-size.

As for the studio itself, this was a garage when Petty bought the place in 1998. Now the space is rather cosier, with its sliding doors, warm terracotta colours, dark patterned rugs and natural-wood details, which fix with the mix of Spanish and American Southwest styles in the rest of the estate. There are still plenty of indications that this is a musician's idea of a man-cave, such as the enviable array of guitars on stands that line the walls of the recording space, the deep-cushioned grey sectional sofa and vintage red Coca-Cola machine in the lounge. Personal mementoes—like a painting whose thick brushstrokes mark it as the handiwork of Petty's friend Bob Dylan—decorate the walls.

Surveying his domain in his not-so-lordly outfit of classic Levi's denim jacket and faded blue jeans, Petty shows off the "world's only indoor/outdoor control room," so named for the patio that lies a few feet from the mixing board. He shrugs off the threat of noise complaints when the door's open and the speakers are loud: "I don't have any neighbours, so I don't worry about that."

It all feels like a safe haven for a self-described homebody, as well as a just reward for career sales of over 80 million and a body of work as treasured as anything else in the history of American rock. That's why it's jarring to hear Petty talk of how it nearly went up in smoke.

"That's how close the fires came," Petty says as he points to a ridge just beyond the red patio stones and a thicket of trees. This was in 2007, when wildfires devastated much of the area. "The smoke was so thick, if you went outside you couldn't breathe." He recalls grabbing what he could after being ordered to leave in a hurry, only to realise upon driving away that "there isn't really any possession that means shit."

It wouldn't have been the first time Petty learned that lesson. One morning in 1987, his house in Encino was set on fire by an arsonist—the singer and his family barely escaped before the place and almost all of its contents were reduced to ashes. As he says, "This would've been the second time where everything I owned was gone. And it never really made a difference as long as everyone was OK."

The Malibu fire was weighing on Petty's mind when he wrote "All You Can Carry." Like many of the songs on Hypnotic Eye—Petty's 13th studio album with the Heartbreakers—it bridles with a stridency and ferocity that were once hallmarks of Petty's music but have been rather lacking over the last two decades. Indeed, it's the anger you can hear in Petty's earliest, surliest songs, be it Mudcrutch's original version of "Don't Do Me Like That" or the Heartbreakers' "Breakdown." And while it might've seemed like a part of his past, right now it feels very much in the present. Petty may be plenty amiable as he plays host in his studio's lounge, but, as he admits, "I'm not Mr Laidback."

The unruly energy of Hypnotic Eye may have been absent from the Heartbreakers' recorded output recently, but it has remained a conspicuous presence in their live shows. In his time onstage with the band during tours like his last UK dates in 2012 or the theatre residencies in New York and Los Angeles last year, Petty still demonstrates his love for "anything that's rock 'n' roll," to crib the name of the song that launched them in Britain. This was in 1977, a year before they got any traction amid the surging new wave back home. Yet the albums in the latter half of Petty's career have tended to be mellower propositions. Certainly, that was as true of such band efforts as 2010's bluesy Mojo as it was of nominally solo outings like 1994's Wildflowers.

But there's no such air of late-life repose on the music of Hypnotic Eye. These songs may arrive the same year that Petty turns 64 but the best of the lot are bold, brash and gloriously loud. The opening salvo of "American Dream Plan B" and "Faultlines" is all fuzz, muscle and rumble, and even quieter songs like "Sins Of My Youth" simmer with tension. Petty's right to marvel at its wildest moments, like the fevered vamping of keyboardist Benmont Tench, or the "ridiculous" solo by Mike Campbell on "Forgotten Man."

"That just fries my brain," he says, his pale blue eyes widening at the memory of hearing his bandmates attack the songs with gusto. Nor can Petty conceal the pride he feels about the album. He even admits he counts it as one of the "special ones" alongside Damn The Torpedoes, Wildflowers and Full Moon Fever. Sipping coffee from a brightly coloured ceramic mug and drawing puffs on a red e-cigarette (and the occasional real one), he settles into the sofa as he reflects on the new LP's creation.

"The songs just started coming out that way," he says. "This album has been made kind of in between tours and the first few tracks were done two or three years ago. They were pretty hardcore blues tracks and really great, but then I started thinking, 'This is going down the same road twice—I'll hold onto those for later.' Then the songs just started determining how people were playing and the sounds they were getting. So at some point early on I started to think, 'Let's just do a real rock 'n' roll album.'"

The Heartbreakers were down with that, to put it mildly. Speaking to Uncut, Tench says he was "really delighted" when he noticed the direction Petty's songwriting was taking. "The material he was bringing in toward the end was much more the very, very guitar-driven stuff," he says. "We've always been a guitar band but this was more that style with hard drums and guitar riffs."

In the keyboardist's view, the new songs were consistent with the music that remains the Heartbreakers' fundamental vocabulary: "the rock 'n' roll of the middle-'50s and the middle-'60s." Yet they also ended up sounding like the Petty and the Heartbreakers of the middle-'70s, too. Mike Campbell, Petty's closest collaborator since the days of Mudcrutch, confesses he surprised the singer when he told him how much the vocals on Hypnotic Eye reminded him of his voice on the first few albums. "There was an urgency in his voice that sounded very familiar," confirms the guitarist.

"I hadn't thought of that, but he was kinda right," agrees Petty with a smile. "That's the rock 'n' roll voice."

Petty himself is given to wonder who exactly that voice belongs to now or why his signature snarl is back in the picture. "Maybe it's an angrier, more worked-up kinda guy," is all he'll admit. Thanks to the singer's affable Southern charm, it's easy to forget what a live wire he used to be. After all, he was ornery enough to incur the ire of the music business at least twice over. On the first occasion, he declared himself bankrupt to get out of punitive early contracts on the eve of Damn the Torpedoes' release, and then by warring with MCA over their plans to introduce a higher LP price with Hard Promises. "I did go through a lot of my life with a short fuse where I could erupt into a serious rage," he admits. "I think that was a product of my childhood, where I had some serious abuse."

Petty chalks up much of that darker energy to his physically abusive relationship with father Earl growing up in Gainesville, Florida. As much as it fueled his musical ambitions and bolstered his determination to stand his ground, his anger could cause considerable trouble. The most dramatic evidence came in 1984, when he vented his frustration during the Southern Accents sessions by smashing his left hand into a wall and pulverising many of the bones within. Eventually, he turned to therapy to help take the edge off the old traumas. "I started to learn and retrace what had happened to me and why I was that way," he explains. "It became quite clear to me why. And once you know why something is happening, you know how to fix it. Now I don't lose my temper and, God, it's a lot better life."

According to Petty, the only good thing about getting old is "the wisdom part." As he explains, "I don't have many debates with drinks on barstools any more. That's my shorthand for somebody who's just a waste of time, somebody who's just talking bullshit to me. I just walk away."

Petty now prefers to channel the rage of his younger self into characters, guys like the pissed-off narrators of "Burnt Out Town" and "Forgotten Man." Then there's the youngster in the album's opener, "American Dream Plan B," a kid who's "half-lit and can't dance for shit" but is still determined to get what he can in an era of diminished expectations. Elsewhere, panic and dread colours songs like "All You Can Carry," and the album's eerie closer "Shadow People"; clearly, this is an album that's not just louder but darker and more despairing than many of its predecessors. As usual, the prominence of Petty's melodic gifts and wry sense of humour are two mitigating factors. But by their author's estimation, the songs reflect the world as he sees it in an age of widening disparities and a public enthralled to the false values of tech and celebrity. (The album's title refers to a camera-happy populace who barely notice they're being controlled by the gadgets they love.)

Petty leans forward to put his mug on the wide coffee table in front of him, his manner less relaxed as he mulls the state of things beyond the iron gate at the end of his driveway.

"I'm not really a political person but I am a practical one," he reveals. "It is easy to see the good guys and the bad guys right now even though the good guys are a little grey.

"But I remember when people made a living and were quite happy and didn't even want a swimming pool but they were fine. You could do an honest day's work, support your family and maybe even own your own home—you could get by nicely. And as that's been taken away, a desperation creeps in. Then you have the media trying to hypnotise them by telling them, 'No, you should be rich or you're nothing. If you're not dressing like Kim Kardashian, you're nothing.' And that offends me."

His laughter suggests that he's aware of the irony of expressing these sentiments while enjoying the comforts of Malibu living, complete with a beach house closer to the ocean. But Petty still remembers what his life was like growing up in Gainesville, or driving cross-country with barely any gas money as he tried to rustle up interest in Mudcrutch. He presses one of his dark suede shoes against the table as he speaks. "I've been poor so whenever I hear somebody say, 'Oh, money doesn't matter,' I think, 'Well, that guy's never been poor because that's a stupid statement.' But y'know, it's nice to be able to pay your bills and not having to sweat it out all the time, because that's most people's lives. I don't take that for granted. I feel very blessed and happy. But I don't think money was ever the important thing for us."

Petty also understands the ultimate worth of his worries about where things are headed. "I can't save the world," he says, breaking up once again. "I can only bitch about it!"

Outside the studio's lounge, the sun breaks through the haze typical of Malibu in the early summer, adding a little extra colour to the well-manicured lawn beyond. Petty slides open the door to toss his cold coffee onto the stones and returns to the sofa to continue with the conversation. For all the rancour he expresses in Hypnotic Eye, it hasn't seemed to impact the prevailing air of contentment among the Heartbreakers. Made to mark the band's 30th anniversary celebrations in 2006, Peter Bogdanovich's four-hour Runnin' Down A Dream film recounted the group's sometimes stormy history in exhaustive detail. But any signs of internal strife—like the strains when Petty stepped out of the fold to make Full Moon Fever with Jeff Lynne—seem deep in the past at this point.

"It's pretty much a love fest," explains Petty. "It's almost embarrassing how well we're getting along—let's just say it's the complete opposite to what we were in our twenties! Everyone really appreciates this thing right now. We're lucky boys to be alive after what we've been through and to be able to do our thing on the level we want to do it. And I never dreamed we'd be doing it this late in our lives. We're all very grateful for that."

Mike Campbell believes it's only natural for the bandmates to have developed separate lives over the decades even as they've maintained the essential bonds. "Months will go by and I may not speak to Tom much," admits the guitarist. "And then we'll get on the phone and talk for two hours—we have that kind of relationship. We don't socialise that much—we don't go out to basketball games or movies or dinner too often. But you gotta give it a break every now and again. Bands are very delicate. If you love each other and you love what you do together, you have to protect it and give it space."

"Blood" is how Tench describes the bonds within the band. Even so, he was still moved by the support he received from his bandmates when he performed a Los Angeles club gig in support of his debut album, You Should Be So Lucky. Says Petty, "I went down to see the show and I felt so proud. He was really good and he had a great little band and the audience just went mad for him. You'd have thought he had done this his entire life the way he was so comfortable onstage and being up front. I was shouting at the top of my lungs for him."

Tench admits it was intimidating to have the Heartbreakers in the house. "It's like having a party with your pals and your older brothers all show up," he jokes. "It's like, 'I better be sure I'm on the money tonight!'"

Petty was amused to be on the other side of a familiar situation when the Heartbreakers were asked to leave Tench's dressing room so he could get ready for the show. The band reconvenes for their North American tour in August and Petty hopes they'll play with the same spontaneity they brought to the dates in New York and LA last year. "There weren't really arrangements for a lot of those older songs," he laughs. "I knew I was starting in the key of C on my guitar and that was it. We didn't know who was taking a solo or when or how we'd end this motherfucker but that put us on our toes. I kinda left there every night feeling, 'Wow, we really played some music tonight.' The band's at a point where we like to be as loose and improvisational as we can. That keeps us interested."

That the Heartbreakers still exude so much vitality is all the more remarkable given the potential burdens of their history. "You carry around a lot with you," Petty admits. At this point, their sets could consist of nothing but much-cherished hits, a prospect that doesn't sit well with Petty. "I ain't dead yet," he cracks. "I'm still doing new music and I insist on playing it. Haven't had a lot of resistance to that."

Yet whether it's going through old tapes to pick the performances on 2009's Live Anthology, delivering a dose of cosmic country-rock with the reconstituted Mudcrutch (which Petty plans to reconvene this year) or preparing a new edition of Wildflowers [see panel], Petty's tended to his legacy with the same care he devotes to his new music. Whatever he carries, he seems to carry it lightly. Here in the studio, that past is on the walls. The space peers may devote to platinum records is taken by more personal totems, like a photo of the host with hero Carl Perkins and the Dylan painting. "I do marvel at him," says Petty of his friend and former Traveling Wilburys bandmate. "Bob's so much better than all of us."

Further along the wall is a shot that Jim Marshall took of George Harrison backstage at Dodger Stadium in 1966. It's hard not to be struck by the fact that Harrison was all of 23 when the picture was taken. Petty and his friends were nearly as young hen the band's rise began. Drawing on an American Sprit cigarette at the tail end of our talk, Petty is moved to reminisce. "We were kids," he says. "It was a great way to grow up. If I look back on it all like it's a film, the part I remember the fondest was before Damn the Torpedoes. The '70s was really great because we were getting to that point where we had an audience but things weren't out of control. We had steady work and we had a loving audience and we felt so inspired—that was the greatest to me. Not that the rest wasn't fun but that was especially so. We didn't have 20 bucks between us but we somehow made enough to live and keep travelling and keep working."

Petty leans forward to tap the ash into an oversized wooden ashtray on the table. "That was one advantage I had over a lot of my friends—by the time I was 15, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. A lot of them didn't well into their twenties. But I knew right away what my calling was, there was no question about it. I had no choice—I was fortunate in that way."

Let Me Up: The Hardest Parts

Petty on the albums that most tested the Heartbreakers

HARD PROMISES | 1981

"That was a hard record because we were coming off this massive hit record [Damn The Torpedoes] and there was some pressure on me to make one just like it. I was determined not to. I was looking for some different ground and it was a very slow process. It was probably a good learning experience. Today, we know so much about the process of making a record that it's disgusting—we could bore the pants off you telling you about that end of it. But in those days we were still learning in the studio and it took us quite a while to get what we wanted. Fortunately, we did and the record was successful, but I was pretty worn out when I got that done."

SOUTHERN ACCENTS | 1985

"'Don't Come Around Here No More' was one of the only times I was trying to make a single. I wanted to get it just right. Dave Stewart and I had a lot of fun doing it but we were on it every day for a month—it's a very complicated record. But it's become one of the most popular songs we play live. The rest of Southern Accents was really hard and that was due to bad behaviour—too many women problems, drug problems, you name it and we had a problem with it on that record. I came out of that record on crutches and with my hand in a cast. I still don't feel like I got what I was really after. I would love to remix some of that."

REVISITED: Wildflowers Rise Again

1994's solo LP reissued—as a double album!

"This is not just some schlocky way to sell the old album," swears Petty of the forthcoming expanded 20th-anniversary edition of his solo Wildflowers LP. "There's a whole other album on there and it's good. We were really on our game then. When I hear it back, I'm like, 'Wow, we didn't put that out?!'"

The product of two years of diligent work by Petty, with Mike Campbell and producer Rick Rubin, Wildflowers was originally intended to be a double-disc set but was slimmed down to a single upon the advice of then-Warner boss Lenny Waronker. Petty later put four of the unused songs on the Heartbreakers' 1996 soundtrack for She's The One—but even those tracks will be heard in very different forms on the new edition, which Petty says will surface later this year.

"When you hear what was really on the tape and the way it was intended to be done, it's miles better.

"'Climb That Hill' was one of those songs. As we were going through the taoes, we found that we didn't even put the right take of that on the album. The one meant for Wildflowers had a different beat. I was so scattered at that point—not my proudest moment!" Petty was similarly struck by the quality of the recordings thanks to Rubin's insistence on capturing live band performances. "God, it sounded so good," he says. "And it was all there—just bring up the faders and voilà, there it is."

American Boys: A Heartbreaker's Who's Who | 2014 Edition

Mike Campbell | Guitar, Bass, Keyboards, Mandolin - Since 1976

Petty's closest musical partner since they were teens in Gainesville. Extracurricular efforts include co-writing "The Boys Of Summer" with Don Henley.

Benmont Tench | Keyboards - Since 1976

Gainesville keyboard wiz who Petty convinced to drop out of college and stick with him and Campbell in Mudcrutch. Has done sessions and tours with U2, Elvis Costello, Green Day and just about anyone else you can name.

Ron Blair | Bass, Backing Vocals - 1976-82/2002-Present

Gainesville native who joined the Heartbreakers along with Stan Lynch. Famously left the music biz to run a bikini store before rejoining around their 2002 induction to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

Scott Thurston | Guitar, Harmonica, Synthesiser, Vocals - Since 1991

Versatile player from Oregon whose pre-Petty career included a long stint with Iggy Pop.

Steve Ferrone | Drums - Since 1995

Brighton-bred musician is the only Brit to serve. Early career includes time with Bloodstone and the Average White Band. Toured with Duran Duran and Clapton, too.

Also Served

Stan Lynch | Drums - 1976-1994

Another Gainesville native who became a Heartbreaker in L.A. Later worked with pals in the Eagles and country artists like The Mavericks.

Howie Epstein | Bass, Backing Vocals, Mandolin - 1982-2002, Died 2003

Plucked by Petty from Del Shannon's band after Blair's departure. Long struggle with heroin addiction ended with death at the age of 47 after being fired for his growing unpredictability.

Honorary Members

Stevie Nicks

Often claimed that she'd have quit Fleetwood Mac if the Heartbreakers would've taken her in. Settled for hit duets like 1981's "Stop Draggin' My Heart Around."

Bob Dylan

Employed TP&TH as both opening act and backing band on tours in 1986 and '87. Was a Wilbury too.

Roger McGuinn

Key inspiration and longtime friend. Petty, Campbell and Tench backed him on much of 1991's Back From Rio.