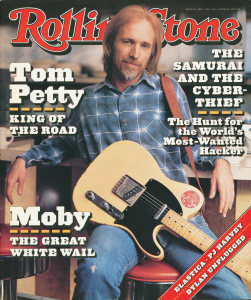

Tom Petty On the Road: This is how it feels

By Fred Schruers

Rolling Stone #707 - May 4, 1995

"That's all we need is another dog onstage." Tom Petty's calm drawl has just gone as thick as black smoke from a smudge pot. Petty is standing midstage in the indoor twilight of his late-afternoon sound check in an aging arena at the University of Notre Dame, in Indiana. Even as he says it, Petty can't quite throttle the conspiratorial smile we know so well from the videos. How many platinum-selling bandleaders get to address this issue?

The Heartbreakers, the 1995 version, stay busy around him. Benmont Tench is adjusting a pair of rear-view mirrors that allow him to watch his band mates when he's facing the Wurlitzer to his right, and Mike Campbell is cranking out trial licks from the 12-guitar array behind the amps. Scott Thurston, utilityman and bon vivant on 3 tours with the band, tweaks his "Thurstophone" keyboard. Steve Ferrone, who has replaced longtime drummer Stan Lynch, listens to Petty as Howie Epstein, bass player and owner of Dingo, the massive German shepherd perched nearby, studiously does not. Petty glances toward the wings, and Dingo cocks his head.

This is the Dog With Wings tour, 52 packed shows on this leg and another three months about to be tacked on. With Petty's second solo album, Wildflowers, headed for the 3 million mark in sales, the line from the track "It's Good to Be King" is hardly obscure. "Yeah, I'll be king," sings Petty, "when dogs get wings."

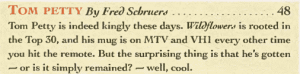

With each week of this road trip, the inside joke makes more sense. Petty is indeed kingly these days: Wildflowers is rooted in the Top 30 six months after its release (the band's Greatest Hits made the Top 5 and still nestles in the Top 100 after 18 months), and Petty's mug is on MTV and VH1 every other time you hit the remote.

Petty has walked, not without some fretting, the fine line between bandleader and solo artist. He and the band collected critics and fans in the '70s, hits in the '80s, and turned the corner to the '90s on the strong surge that Petty's solo hit Full Moon Fever provided. A Grammy nomination for that record and an MTV Best Male Video award for "Mary Jane's Last Dance" are among his trophies, but the thing that has been dawning on pop culture for a while now is that this gawky Florida boy, who's looking ever more like a saddle-weary conquistador, has grown -- or is it simply remained? -- well, cool.

When the band was filling only half the seats in the venues, Petty would say: "The hall's only half-full, but we're gonna play the best we can. We've always been the steady tortoise, not the hare. Keep going, keep hoping."

Thus we find the man talking dogs in this 8,700-seater in South Bend, Ind., three dates into the Midwestern plank of the tour. The prototype dog with wings is sitting 30 feet directly above Petty. Leaper is a giant bronzed Chesapeake, who, technology willing, makes a nightly flight down a metal track above the screaming fans.

But now Petty's wife, Jane, has proposed bringing their 120-pound shepherd, Enzo, on the road. "Do you want to deal with him every morning at dawn?" he asks her. "Every morning when the sun comes up?" Still, it tells much about Petty that he said reflexively on Day One that Epstein's Dingo could come onstage "if he wants to." Doesn't Petty know that you should never share the footlights with kids or dogs? "They just gotta take us as we are," he says. "And that dog's part of Howie's life."

The tour trots on then, still somewhat...dogged by the open question the band faced when they descended on Louisville, Ky., for the first show. Would the people buying so many copies of Wildflowers be the same ones in the crowd, or would audiences be hollering for the '80s hits? Still brooding over the internal strains that led to Stan Lynch's departure, the band has yet to test the new lineup onstage. And what would it mean to have a frontman who's now a twice-certified solo star?

"Groups are a very complicated thing," says Mike Campbell, recalling the first days of Petty's earlier solo shot. "It's like a family, it's like a business relationship, it's a very emotional thing. You care about each other, and you tug just like brothers; you're jealous, and then you love each other. It's a very complicated monster."

Campbell, despite co-writing Don Henley's "The Boys of Summer" and producing Patti Scialfa's album, Rumble Doll, adds that "honestly, at this point in my life, I'm not really interested in working outside the group unless it's on my own stuff. I haven't really enjoyed anything as much as the band. We've got so much to do: the box set and another album and tour and this and that."

The box set Campbell is referring to is a career-long retrospective; the band will halt its tour in June to finish it off for Christmas release. "We're late to turn it in, but Tom said, 'No, let's go out and play.' I was glad to hear that." Campbell gives a tight grin, eyes veiled behind blue mirrored shades. "Tom calls the shots."

The closer you look, the more unshakably together Petty and the remaining two 20-year men seem. Benmont Tench, one of rock's true master keyboardists, has known Petty since their short-pants days ("We go way back to when we were little boys," Petty tells one crowd. "I wouldn't go anywhere without him"). And Campbell has similar stature on guitar. Without his writer-arranger skills, says Petty, "I would be completely lost." But for all his cronies' prowess, Petty, by serendipitously making a string of solo hits, has added much weight to his half of the old frontman-plus-band equation. To play with Petty is to always keep your eye on him. He's the one who says where the seesaw goes and when.

The Heartbreakers are assembled onstage for rehearsal in the drafty Louisville Gardens when Petty arrives, drapes a guitar strap across his shoulders with many seasons' nonchalance and abruptly kicks off a stirring version of the Byrds' "It Won't Be Wrong." It's easily the most beautifully harmonized song of their live set, with Epstein skying along above Petty's vocal, Campbell and Petty's guitars stinging sweetly along with Heartbreaker-for-hire Scott Thurston's. Thurston -- a reed-slim, drolly grinning Midwesterner who has played with everybody from Ike and Tina Turner to Stooge-eras Iggy -- plays harmonica on a run-through on "You Don't Know How It Feels" as Petty turns to subtly conduct Ferrone. When "Love Is a Long Road," the Full Moon Fever track that opens each night's set, runs away, Petty beckons in the band to talk, and both the tour's film crew and a VH1 team lean in, boom mikes poised. Petty slouches, a little North Florida redneck electrical crackle that's felt rather than seen.

"You guys are gonna have to fuck off," he says casually, and both crews retreat. Next, it's "Wildflowers," as potbellied guys in green T-shirts arrive to lounge dully in the front row. "Wow, security's here," says Petty flatly into the mike that sends his voice to every corner of the empty hall. "Great." The way he draws out the last words sends them shuffling off. "You were so cool back in high school," sings Petty on Wildflowers' "Wake Up Time," bearing down on his work at the baby-grand piano he takes over from Tench. "What happened?"

"I'd been nagging Tom to write a piano ballad for this record because we had plenty of guitar songs," says Wildflowers producer Rick Rubin. Indeed, from the first chiming, folkie-style strums of Petty's acoustic on the title cut, the album declares itself a homespun singer/songwriter's effort. Tench's tintinnabulary keyboards as well as a cannily integrated orchestral backup are there only to serve the guitar's buoyant mood. To run down Petty's influences is to enter a nicely appointed maze, but the what-the-hell drumming, whimsical harmonica and telegraphic Petty guitar solos are out of a mid-'60s Basement Tapes ethic for which the recent years of MTV Unplugged have readied our ears.

Petty worked zealously on sequencing the record as he cut 25 finished tracks down to 15; just after the string-section zephyrs of "Time to Move On" threatens to glue the record to the middle of the road, he throws in the garage-rocking "You Wreck Me," a Campbell riff-fest. "Rick suggested this song that Mike had played him," says Petty. "And I thought, 'Man, this sounds just like the Heartbreakers about 1980' -- that style (that tells you) exactly who that is. So I got into it, to do a nostalgic song -- 'All right, we'll go back as far as high school.'"

Rubin calls the Wildflowers sessions "just a casual process of getting together every afternoon for two years." Discovering Petty late -- with Full Moon Fever, which he listened to “5,000 times" -- Rubin saw to it that then Warner Bros. label head Mo Ostin introduced him to Petty when Petty switched to the label. “I just hoped we could have songs as good as Full Moon," says Rubin, “but with more rock & roll, more personal approach, as opposed to a pop presentation."

Rubin jettisoned the sound established by Jeff Lynne, producer on Full Moon Fever and the Heartbreakers' Into the Great Wide Open and, of course, the Traveling Wilburys. Rubin banned synthesizers, any nonacoustic keyboards and the overdubbed, metronomic drums of those records. Although Rubin, Petty and Campbell did ultimately make a record for the rock bins -- as when the unabashed Byrdsy chords of “A Higher Place" yield to the bluesy grunge of “House in the Woods" -- Petty clearly did call his own artistic shots with the likes of the whispery “Crawling Back to You." The battered character of that song is a clear emblem of Petty's emotional maturity and looks backward to the angry, passionate trail he blazed through romance in “Fooled Again (I Don't Like It)" and “Don't Come Around Here No More." That anger gradually yielded to the almost psalmlike “Free Fallin'," the bittersweet “Learning to Fly" and “You and I Will Meet Again" to arrive at the nearly Zen-like resignation of Wildflowers.

Once Petty has rehearsed “Wake-Up Time" in Louisville, the crew begins igniting banks of light, testing their cues, as the band, sans Petty, blitzes through the hairpin turns of the Ventures' surf workout “Diamond Head." In the set the song allows Petty to run off for a couple of minutes while the audience lets Campbell, as Jane Petty says, “put a little culture on 'em." It recalls the precocious virtuosity Campbell showed 25 years ago when he first got out his Goya and jammed on “Johnny B. Goode" with Petty's band the Epics. “We just went, 'Holy shit,'" says Petty. “He was smoking. At the end of the song, I just said, 'Well, you're in our band, man.' And he was, 'Well, I'm going to college.' 'No, trust me, you're in our band, and you're not going to college anymore.'"

“I have to thank him for insisting," says Campbell. “I took my tuition and bought a guitar. That was it."

It's almost time for a sound check when Petty slinks through the wood-paneled lobby of an old tobacco-men's hotel to make the short bus tide to the first gig. He seems oddly cheered by a file of what he takes to be nurses gathered near the hotel door. Martyn Atkins, the English graphic designer (he did the Wildflowers cover) and filmmaker, is hoisting a camera onto his shoulder. “I think those are Clinique, ah, makeup girls, actually," he explains to Petty. Field commander Petty, frisky, can go with that: “It was like inspecting the staff."

At the hall Petty unpacks a couple of trunks (“I end up wearing one or two shirts the whole time anywhow"), talking about how you can tell you're in the Deep South -- “We passed about 50 wig stores on the way into town" -- when wardrobewoman Linda Burcher greets him. “Here we go again," he says. The band's an easy gig for Burcher (“It's pretty much go up onstage in what you're wearing throughout the day," Epstein later points out), and she complains to Petty that her last “hair band" job involved many blow-dryers. “We all wear wigs," Petty smirks.

He has never been the likeliest rock star. When the sitcom Wings was striving for a moment of high hilarity as some good ol' buys tried to name a truly handsome man, the most oafish one picked Petty. The pipestem physique, the big old head, the sea-oats hairline that has been subject to various hat and bandanna stratagems, all yield to an overbite of some grandeur.

“I didn't get into this to be a pinup," says Petty in his quiet, gravelly voice. “I wanted to be taken seriously as far as writing songs, making music. The other thing limits your run, really. Some people are so good-looking they can't help it. But I'm certainly not" -- the signature slow grin -- “saddled with that problem."

Well, perhaps, but the girls who promised to “tear you apart" in the Byrds' “So You Want to Be a Rock & Roll Star" will become a force six dates into the tour, in Chicago, lurching against the stage-front barricade. By Pittsburgh, four cities later, “it was craziness," says Petty. “We actually had two teenage girls tackle me midshow, which amused us all."

The welcome surprise for Petty thus far on the tour has been that he's “really getting the feeling they'd rather hear Wildflowers than anything else. I think a lot of people out there know us mostly from this last album."

But on opening day in Louisville, such insights have yet to be gained. “We're skipping all of the mid-'80s stuff," Petty says almost blithely. He's still unpacking alongside Jane as she comes upon the previous tour's rubber gator head (the “psychedelic dragon"), saying, “What is that thing doing here?"

“Is the band here?" Petty asks as the time for sound check nears. It's not generalship but a need to touch base. “They don't call, they don't write," he mutters, shivering a bit in the chill of the hall's concrete underbelly. When he appears onstage, it's with the austere ceremony of a quarterbnack arriving at the scrimmage line, a simple round of nods and discreet hand gestures -- except for Ferrone, who out of new-guy eagerness, claps a hand on Petty's shoulder. “We might come in a room and hug and kiss everyone in the world except each other," says Petty later. “To me, that's reassuring as to how close we really are. It's like brothers."

There's a certain gunslinger aspect to the way the band arrives before a gig, usually via three buses that grind the few blocks from hotel to hall, then roar out on a ramp and on to the next city seconds after the group has left the stage. Petty and Jane's bus often carries longtime manager Tony Dimitriades and the odd stray guest; Epstein, always accompanied by Dingo and sometimes by his wife, Carlene Carter, has shelled out for his own; and the rest of the band takes a third -- although the whole contingent might pile in to one bus for, say, a Chinese-food binge.

Each night, Petty hangs with Jane behind a DO NOT DISTURB sign until a half-hour prior to show time, first having a snack, “then I look over the set list and decide what we're going to play. And then I'll warm up my voice for a while with my acoustic guitar, go into the shower where the echo is nice and warm up for maybe 20 minutes, just get confident that my voice is working well. Then I'll get dressed for the show; I always get down for the last 10 or 15 minutes before we go on and hang with the band -- try to catch a group vibe before we go up. At least it's collective nervousness at that point."

In the band's dressing room an hour before the gig, Tench and Campbell torture Ferrone while Thurston grins to himself. They talk about “one gig and out," what Ferrone will do when he's kicked off the tour, until the tall, handsome drummer's indefatigable grin freezes into a pained rictus, and he goes into the shower -- a longtime ritual -- strips and soaks, hollering songs of his own choosing. By the time he's pulling his clothes on, a velvet-jacketed Petty strolls into the band's lair, strumming the acoustic strapped over his neck. “My sister got lucky," he sings, giving that sideways look, “married a monkey...." He wheels around the corner, catches the echo from a nearby shower and keeps pacing. With scant minutes left, Ferrone hauls in some deep breaths and puffs them out. Tench, eyeing his amusedly, sings: “My sister got lonely/Married Ferrone-ly...." with that, the new guy breaks into a grin about the size of a Buick Six grille.

“Steve's fit in really well -- a real 'up' guy," says Campbell a few days later. “I haven't seen a dark side yet to his personality. A few more weeks on the bus, who knows? But he's a great player. He's slowly figuring out that there's times when we just want pure air to move, forget what you're doing with your left, right hand, we just want some thrust. Stan was real good at that. I'm hoping that Steve'll do more of that as he learns what we like."

The departure of Stan Lynch seems to have its roots in the aftermath of a long spell when the Heartbreakers toured behind Bob Dylan (and played on his Knocked Out Loaded) circa 1986. After what Petty describes as “two years of constant, grueling touring," he had come home with no great urge to bring the band into the studio. The phrase “full-moon fever" was his code for doing something whimsical: “The solo record was almost accidental, like 'I've got to do something where I'm not obligated to anyone but me.'"

“The timing of that project was not the best," recalls Campbell, “because we had been discussing how we were going to start this next record. On the break, Tom met Jeff Lynne at a stoplight near his house, and they got together and wrote this song, called me up and said, “Can we come over and play around with this song?' And within a week there were four songs."

By the time Tench got wind of the sessions, his band mates were on a full-blown project. “I remember that I was angry," the keyboardist recalls. “My feelings were hurt. But things happen. If you wait through it and try to understand, it can be all right. And if you let your ego go crazy, you wind up shooting yourself in the foot. The band's too good to blow it up."

Tench, of course, ended up pitching in: “I showed up for 45 minutes and played one song." Still, Campbell, whom Petty has described as his lieutenant in the band, empathizes. “It's just being human," Campbell says. “I totally understand how Ben feels.... Nobody's going to hold it against him, because this band is our whole life."

Despite his jobs as visiting virtuoso for endless sessions, Tench says, “The band is the most important thing to me. And everybody I've worked with, the deal has been, I will absolutely be there 2 o'clock Wednesday afternoon -- unless the band's doing something." Lynch got no session invite at all, and “speaking candidly, I don't think Stan ever got over it," says Petty.

“Stan and I always had a turbulent relationship, but it was part of the magic," Petty continues. “But there came to be real tension in the music. We honestly couldn't function with each other. I did get mad at one point and sort of pushed him, but I didn't fire him. Stan needed a little shove to make that decision, and I only shoved because of the pain I could see him in, which eventually was causing me pain and problems. In a way, Stan left the room without saying goodbye. I said to him, 'Hey, listen, man, a 20-year run is pretty good.'"

Tom Petty was age 12 when he met Elvis Presley on a movie set near Gainesville, Fla., and one hand-me-down box of Elvis 45s and the classic first guitar later, he was irrevocably hooked: "My parents were actually disturbed by the extent to which I went into it -- because I had no interest in anything but that," Petty says. Employed at the local music shop, Petty presided over young Benmont Tench's recitals ("I was the annoying kid who would sit around and play the piano," Tench recalls). The son of a judge, Tench went off to prep school, then college for a spell.

When Petty was 14, "I got in this band called the Sundowners -- an English Invasion-type band. Then in '66 I went to a band called the Epics -- playing bass, and occasionally I got to sing 'Love Potion No. 9' and 'Like a Rolling Stone.'" From the Epics came Mudcrutch ("really one of the worst names ever in show business") in late '69.

Armed with a sack of tapes of a two-track demo cut in Tench's living room, Petty took off for California in a van with a band mate and a roadie. "I stayed behind," says Campbell, "because there wasn't enough room in the van. But I gave my rent and food money for that month for the cause. I stayed back to sort of keep an eye on the girlfriends."

The next stretch is an oft-told history -- the collapse of the band's deal; Petty's apprenticeship as a songwriter for Leon Russell; the magic day when Petty stopped by Tench's demo session and realized he was looking at his band (founding members Tench, Lynch and Campbell); the slam-bang sessions to make their first album. They thought they could better the pap that dominated the airwaves, and they did. "American Girl" and "Breakdown" poured out within days of the band's start-up. The Petty who poses on the cover in black leather and bullets projects a sly attitude, and the record was "a floodgate of influences, of everything we'd ever admired and against what we thought was wrong with the music of the time," says Petty. "And suddenly, there were a lot of people who thought the same, and we could really play. In the South if you couldn't play, you didn't work."

In mid-'60s northern Florida, a place that was more like red-clay Georgia than Miami, crackers still ruled, and Tom Petty knew all the other longhairs in Gainesville. "It was just a nice little suburb," he recalls. "It wasn't even middle-class families, really, but very small cinder-block houses with lots of trees. I'm a creature of the suburbs."

His father had, in fact, moved from Georgia down to Florida. "My dad's mother was an Indian [Cherokee]; she was a cook in a logging camp, and she married a logger, and they got into a fracas over interracial marriage. My grandfather killed a guy, another logger, so they fled Georgia down to Florida, and that's how we wound up there." Petty's father, Earl, went into insurance sales but was still of people who worked with their hands. "Very much so -- a lot of rough edges," says Petty. "He's quite a colorful character." It was Earl who supplied the phrase that gave birth to Petty's "Don't Do Me Like That."

"My mom also came from Georgia, but she was of French and English descent," says Petty. "How they hooked up I can't imagine -- they were completely different people." Living in Gainesville "was almost citified for my family," adds Petty, who doesn't know as many cousins "as I probably should. Some of us came out of the woods and some of us didn't."

Although he thanks God in the album credits on Into the Great Wide Open, Petty is not a churchgoer. "They tried," he says of his parent. "Southern Baptist, they were. I never really liked it much. I got nothing about God. I just found way too much hypocrisy there. But I do think I got a lot of the rock & roll stage-show stuff from watching those preachers as a child."

Petty has one brother, seven years younger. "He's in sales, a normal job." After the Elvis meeting and regular doses of the Beatles and the Byrds on radio and TV, Petty became "kind of an abnormal kid -- like 'This is what I really love doing.' I made a whole new circle of friends, and it didn't have much to do with school or other kids my age. The simplest little things were so magical -- still are. Learning 'Wooly Bully,' you know, and sitting there late at night going, 'I could make another song out of this,' was like a bolt of lightning."

By the time Petty's "Anything That's Rock & Roll" became a hit in England and the band toured to frenzied crowds, Petty's mother "started seeing that, wow, things are working out for them." When she died in '81, he reluctantly skipped the funeral. "Gainesville was just manic for me to even walk the street," he recalls. "I just didn't want to disgrace the ceremony with a circus."

Petty's mom did see the success of the band's third, breakthrough record, 1979's Damn the Torpedoes. "Refugee" was perhaps the most unforgettable among several hits and is the key song from that era that the band's playing in concert now. "It's kind of like our 'Satisfaction,'" says Petty. "You have to do it, like Ray Charles has to play 'What'd I Say.'"

The hits didn't make life simple. Petty readied the next album, Hard Promises, only to go to war with MCA over their proposed $9.98 asking price. He blocked the dollar price hike on his record. "I'm sure I could have made tons more dough by just doing really honky things." MTV and Petty discovered each other around 1982 (the Mad Max-style "You Got Lucky" was one of the first narrative videos), and on the surface, life was easy. But success led to a kind of overripeness, and Southern Accents, the record that began in Petty's home studio, turned into a frustrating band mire.

Petty admits it was a whiskey-soaked period: "Very much show, and everything else there was to be soaked. When we stopped touring in '83 for a couple years, we hadn't known any life off the road for a long time. And suddenly, OK, I built the studio in my house, and we can record all the time, we've got a big clubhouse now. And the whole world comes to you."

Amid the soakings, Petty cut the heartfelt title track, and pinch-hit Dave Stewart, who'd become a neighbor, helped him craft the tastily psychedelicized "Don't Come Around Here No More." Spurred by the horns Robbie Robertson had come up with for "The Best of Everything," Petty took a big band on the road.

"We were right off the tracks then, all of us," he says. "I remember hiring all those people and not even rehearsing them -- you know, 'Just play along.' Southern Accents in general was a wilder kind of wild because we were wealthier and more powerful than we had been when we were doing 'Breakdown.' Everyone had their own set of problems. Like, 'I don't know if anyone's noticed, but Benmont's facedown in the aisle of the bus. And he hasn't moved for a long time.'"

Notoriously, Petty stamped the last days of the Southern Accents sessions by whacking his left hand against a wall over a mixing session gone awry. He now has metal where he powdered the long bones between finger and wrist. That costly lesson "came right on time," he says. "I think we all took a few wounds on that album."

You could still hear the pain on 1987's Let Me Up (I've Had Enough) and the Dylan-driven single "Jammin' Me," and Petty and the band found themselves somewhat becalmed in the months before the next turning point -- a house fire in May 1987 that damaged Petty's studio and took his dwelling -- and almost his life.

Scarily, police pegged the blaze as arson. "But the joke was that it really restored me and fortified me more than anything else in the world could have at that time," Petty says. "My life changed, the whole tone of my music changed. That anger went away. You hear Full Moon Fever -- it's a very happy, pleasant and positive album and was meant to be so. And that was a result of just being so glad to be alive." The album's first single, "I Won't Back Down," epitomized the new Petty, and the third single, "Free Fallin'," certified what he calls "a complete rebirth with a whole different audience, a younger audience."

It was also circa 1987 that Petty put down booze for good. "I've never been in a program," he says. "I don't know if I'm cut out for it. It really wasn't that big a challenge. I just didn't feel like doing it anymore, so I stopped. I feel so much better." The Pettys' sometimes strained marital relations, including a spell or two of separation, also eased, and he and Jane nowadays are the picture of togetherness. (When she comes to the front of the bus to drawl, "The king needs an ashtray," any sarcasm is completely smothered by the fondness in her tone.) "But," admits Petty. "we have taken some shrapnel. We do walk with a slight limp."

Petty is loping down a long tunnel toward the stage in Chicago, surrounded by Heartbreakers and hearing a gathering roar through the concrete walls as the houselights go down. He's feeling "a little funky" from a cold and what's more, "these guys wanna do 'Breakdown.'"

And they'll get their way, although Petty, in lieu of the song's old mike-whacking frenzy, simply turns and folds himself up in a morose bug while the dimming lights and his subtle nod cue Steve Ferrone to tap the song to an end. Still, once 1995's prolonged tour is done, says Petty, "I'm going to make a real rock & roll album, you know, like an album of all fast songs. A big, loud one."

Anybody who saw Petty's band bashing out "Honey Bee" on Saturday Night Live, backed by Nirvana's Dave Grohl, can picture it well. Grohl's frenzied power, says Petty, "is from another world. He's such a great musician. I've never played with anyone who plays the drums like that." As for the late Kurt Cobain, "I'll tell you one thing, he was better than everybody else.... Now and then you get a real one."

Petty was "very flattered, very moved" by the thrashed-up You Got Lucky tribute album of Petty covers -- "much more than if a bunch of pop stars had done it." He's quite sure he has gotten across to a new generation of fans by never pandering to them. That doesn't mean he won't rock out: "I'm 44 now," he says, "and I don't feel like I'm too old to do it. I don't want to try to act like a teen-ager, either. I would be embarrassed by that."

Happily wrung out after a Chicago show where the encore included the Slim Harpo-style grunge of "Honey Bee" ("Lust is a strong drug") and the farewell lullaby of "Alright for Now," Petty sizes up the pilgrim's progress in which Wildflowers is a chapter: "I can still get very angry and be very cynical. I have to really work on that. Because I am wise enough now that I know that's a waste of time, that cynicism really doesn't advance the project. It's like pessimism. It offers nothing.

"'Good to Be King' is real central to what I was thinking," Petty continues, "how people get so obsessed with that drive to be king, to be wealthy or powerful, as if that might solve their problems. But it's nevertheless kind of an instinct that we all seem to have.

"It's also just a big daydream," Petty says. "Maybe a man's king when he's fallen in love and raised a family. Maybe that's the greatest reward there is in life." He allows himself a last wry smile. "And, strangely enough, available to anyone."