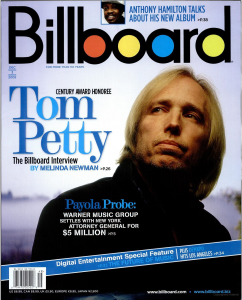

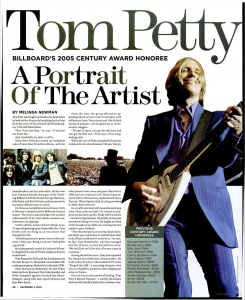

Tom Petty: A Portrait Of The Artist

By Melinda Newman

Billboard - December 3, 2005

Billboard's 2005 Century Award Honoree

Tom Petty just laughs and shakes his head when he looks at the 26-year-old smirking back at him from the cover of Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers' 1976 self-titled debut.

They "were just boys," he says. "It was just too much fun."

And thankfully, he adds, it still is.

Since then, Petty has racked up worldwide sales of more than 50 million albums, with the Heartbreakers and as a solo artist. He has won four Grammy Awards; been part of the Traveling Wilburys with his heroes George Harrison, Bob Dylan and Roy Orbison; and journeyed on too many sold-out tours to count.

For those accomplishments and more, Petty is this year's recipient of the Billboard Century Award. The honor acknowledges the creative achievements of an artist whose musical contributions are ongoing.

And for all this, we have Elvis to thank. As an 11-year-old growing up in Gainesville, Fla., Petty briefly met the King in an encounter that changed his life.

"Everything became pretty clear at that moment," Petty says Being a rock star "looked like a great job."

He subsequently traded his beloved Wham-O slingshot for a box of Presley singles and never looked back.

Petty formed his first band, the Sundowners, by the time he was 14. He landed a record deal with a subsequent group, Mudcrutch, in the early 1970s.

After that group disbanded, he and fellow Mudcrutchers Benmont Tench (keyboards) and Mike Campbell (guitar) formed the Heartbreakers, along with Stan Lynch (drums) and Ron Blair (bass).

From the start, the group offered an appealing blend of lean rock'n'roll laden with influences from '50s rockers and '60s British Invasion groups -- all wrapped up in three-minute nuggets.

"You get in there, you get the job done and you get the hell out," Petty says of his songwriting style.

While the core of Petty/Campbell/Tench has remained in the Heartbreakers' 30-year history, other players have come and gone. Blair left in 1982 and was replaced with Howie Epstein. Lynch left in 1994 and was replaced with Steve Ferrone. When Epstein died of a drug overdose in 2003, Blair returned.

In a world saturated with manufactured pop stars, Petty is the real deal. His refusal to compromise has lead to public feuds with his labels -- and a few legal bumps. Musically, he has also insisted on doing it his way. He laughs out loud at the thought of an A&R exec coming into the studio to give feedback.

"The Heartbreakers are not that kind of people where you could come in and tell them what to do. [That] would just be a joke to us," he says. In fact, Tony Dimitriades, who has managed him for 29 years, is even barred from entry: "We told Tony we'd fire him if he ever came to a session."

During the last few years, Petty has expanded his resume to include actor, DJ and author. He is the voice of Lucky on the animated TV series "King of the Hill," a recurring character who lives on disability payments after slipping on urine in Costco.

He is in his second season of hosting "Tom Petty's Buried Treasure," a weekly, 60-minute show on XM Satellite Radio that combines classic songs, obscure cuts, and live tracks.

Additionally, Omnibus Press has just released "Conversations With Tom Petty," a career-spanning tome by Paul Zollo.

In an interview in his home studio in the Los Angeles beachfront community of Malibu, Petty is a low-key, gracious host. Accompanied by a steady stream of cigarettes and coffee, he recounts his career with humor, grace and a few flashes of regret.

At 55, he is young enough to still rock'n'roll, but old enough to know he is one of the lucky ones. At times, he seems still unable to believe that fate, hard work and magic have brought him to this point.

Petty's third solo album, "Highway Companion," is slated for release this spring. Although there has been speculation that he is leaving Warner Bros. Records, his home since 1994, at press time he is still signed to the label.

Petty will receive the Century Award Dec. 6 at the Billboard Music Awards in Las Vegas.

The Century Award joins a number of other honors: in 1999, Petty and the Heartbreakers received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and in 2002, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The inaugural Century Award was given in 1992 and was named for the imminent 100th anniversary of Billboard in 1994. Then-editor in chief Timothy White, who died in 2002, created the award in conjunction with then-publisher Howard Lander.

Q: Were your parents musical?

A: No. I don't remember much music in my house. My mother would play Nat "King" Cole, some Broadway stuff, "West Side Story" and spiritual stuff, George Beverly Shea, but nothing that super interested me at the time, so I think it was Elvis that got me interested in the music.

Q: You met Elvis on the set of "Follow That Dream" when you were 11. It sounds like he changed your life.

A: He certainly did. [laughs] You weren't prepared to have your life changed in a minute. It really had that sort of impact. It wasn't like meeting Jesus, but it was close.

Q: What did you think when your parents gave you your first guitar?

A: I had always thought guitars were cool because of cowboys. Cowboys played guitars. And Elvis played guitar, so I just thought, "Hell, I'm gonna need one of those." It wouldn't be until a few years later, I guess with the Beatles coming, [that] I really got serious about learning.

Q: How did seeing the Beatles on TV for the first time affect you?

A: That was when the world turned to color from black and white. All of a sudden Technicolor. I was 13 or 14, and I knew exactly what I wanted to do with my life, no question. It still baffles me a bit as to why the lightning bolt hit me, but it did.

Q: Your first band, the Sundowners, started playing gigs when you were 14. What was it like the first time you played in front of an audience?

A: It was an incredible high, and still is. My mom was flabbergasted at the money I was making. I mean, honestly, when I think back on it, there were probably times in my teenage years when I was making as much as my dad. That was probably real insulting.

Q: In the Paul Zollo book, you tell a story about how Mudcrutch played in the Gainesville club Dub's six nights a week, five sets a night. Your dad snuck in to see you, but did not tell you until two days later.

A: Yeah. he was like that. He had a front about this was the wrong thing to do, but he would be seduced by the music. When he saw us do it, he was sort of proud, and it would melt his exterior a little bit. To throw down and come right up front would have been too much for him. He had to be cool, so he snuck in and watched.

Q: With that experience under your belt, you headed to Los Angeles and got a record deal right away. Did you feel like the streets were lined with gold?

A: In those days, you could go down Sunset Boulevard, and they were right up front -- MGM, RCA, Capitol was down the road, and A&M. I remember going into MGM Records. They wanted to make a deal for a single. The same day we went to London Records, they wanted to make an album.

Q: How did you end up on Shelter, which was run by the famous British producer Denny Cordell?

A: We left a tape there with a girl called Andrea Starr. She thought we were cute. By the time we got back [to Gainesville], Denny called and said, "I'd really like to sign the band." I said, "We've already kind of given our word to London." He said, "If you're going to drive from Florida to L.A., it wouldn't be far out of your way to stop in at Tulsa, Okla. I have a studio there, and let's meet each other and see how it feels." We really fell in love with him. We played for a little while, and he said, "That's it, I want the band." And then he threw down some cash: "Here, here's a couple thousand bucks, you're going to need a place to stay."

So we were like, "OK, we're in." We drove the rest of the way to L.A. and drove right up to Shelter Records, right off the freeway, covered in dust, and it's really kind of fairly tale stuff. They really nurtured us along for a good year or so before he even let us make a record.

Q: But it was an extremely one-sided deal in Shelter's favor. A few years later, you had to fight to get out of it.

A: We didn't think it was bad, because we all got new amplifiers and we had a house with a pool and somebody paying the bills. It wasn't a bad deal until we started to sell a lot of records. So it was really kind of the price of an education. You know, some days it really pisses me off, but it's probably fair in the long run. Because he really did save our lives in a lot of respects. Had we made a record the minute we hit town, it probably would have come and gone, and we would have been back playing clubs in Gainesville.

Q: After one single for Shelter, you left Mudcrutch and started a solo album. But ultimately, the Heartbreakers formed. How did that happen?

A: Benmont was trying to get a record deal, and he had gotten some studio time. He really handpicked the Heartbreakers. They were all Gainesville guys who had moved out to L.A., so I was invited to play the harmonica. I went by the Village Recorder in Santa Monica, and I was like, "What a band!" And being the cunning businessman that I am, I said, "You know, backing up Benmont's fine, but there's no reason you couldn't have me in the band and I have a record deal, so you can circumvent the whole try-to-make-it thing and go in with me," and we were off.

Q: The band's self-titled debut comes out in 1976 on Shelter and does nothing in the United States, but album track "Anything That's Rock 'n' Roll" takes off in the United Kingdom, so you headed over there.

A: We went as support act for Nils Lofgren. We got on the covers of the music weeklies and NME, and we did "Top of the Pops" on the TV. We were beyond thrilled. By the time we left England, we were a headlining band, and then we flew home and got off the plane, and you're nothing again.

Q: You came back to the States and were playing for sometimes tiny crowds, as few as four or five people in Boston. Was that disheartening?

A: We thought it was wonderful that we were getting to go around America and play. We had enough buzz to play the Whisky a Go Go, and we started playing [there] as an opening band for Blondie, who were also unknown, and, really, by the end of that week it just exploded. There were lines around the block.

Q: Early singles, like "Breakdown" and "I Need To Know," set the tone for your career. Why didn't you put more of your really beautiful love songs and ballads out as singles?

A: Something that irritated me later on was that [my labels] always went with something that was uptempo and had an electric guitar on [it]. In the last days of FM just before it just died, it used to drive me nuts; if there wasn't a guitar solo, they didn't want it. So something like "Angel Dream," which has got to be one of my 10 best songs ever, was completely overlooked. But, you know, this is life in the big city, what can you do?

I don't think we had a hit ballad ever until "Free Fallin'." And I remember with that, there was some question. I went on "Saturday Night Live," and the single at the time was "I Won't Back Down," and I played "Free Fallin'."and MCA was just furious at me. But my thinking was, "'I Won't Back Down' is already a hit, let's play something they don't expect." I'm sure it helped the record later. Sometimes you gotta do what you think is right.

Q: While you were making your third album, "Damn the Torpedoes," you were fighting to get off Shelter and its distributor ABC. Was the studio your refuge where you could get out all your anger?

A: Probably. It certainly had an impact on what we were doing. This record started in 1978 and didn't come out until late '79, so we got into this protracted legal battle to the point where we were almost stopped from performing. We had to go into court and plead that we needed to perform to live. We declared bankruptcy... it was really a farce. The thinking was if you declared bankruptcy, all contracts would be void, and we saw this as a way out. [We said], "We're unrecouped this much money, and [with] this royalty rate, it would take us 10 years to pay back the money, so in essence, we're bankrupt." But we played it for all it was worth ... I don't think I would do something like that today. I was just stubborn and worked up, and I did see what we're going to do all this work and we're going to have all this success and we're not going to get paid for it.

Q: The Heartbreakers made "Damn The Torpeodes," your first album for Backstreet/MCA, with Jimmy Iovine. What do you look for in a producer?

A: I really look for people I get along with. The best ones know [that] without the great song, all this is a waste of time. You can chrome a turd, you can do every little trick you've got, but if I can't play [the song] to you on the piano or the guitar along, it's not going to work.

Q: Do you see your songwriting ability as a gift?

A: Yes, absolutely, It has to be a gift, because why would I be able to write a song instead of someone else? After a while, you come to realize, "I've really been blessed, I can write these things and it makes me happy, and it makes millions of people happy." It's an obligation, it's bigger than you. It's the only true magic I know. It's not pulling a rabbit out of a hat; it's real. It's your soul floating out to theirs.

Q: When "Damn the Torpedoes" hit, it catapulted you to another level of exposure. Did you want the fame?

A: Sure. I think everybody who does this wants the fame no matter what they say. I would have been very disappointed if I wasn't famous after all that work.

Q: With your next album, "Hard Promises," MCA decided to raise the price to $9.98, up $1 from the standard price. You refused to release it at the higher price, leading to a very public battle with the label. Why did you take that stand?

A: I did it because it was going to be the first $9.98 record, and I was going to be the guy through the door who raised the whole thing, and I thought, "You're not doing it to me, do it to Olivia Newton-John or somebody...but you're not going to do it to me." [laughs] And then it became a bigger crusade than that, and the press got interested in it and so, you know, we saw it through and got our way eventually. The music has to be affordable. It's the common man who keeps it going, and if you price it out of his realm, it becomes a thing of the elite.

Q: Did you worry about losing your career?

A: I didn't worry about my career ending, but there were days where I felt pretty beat up by it all and just pretty tired, because they didn't make it easy for me. And coming right off the last lawsuit, it was the last thing I wanted to get involved in. When it was over, we didn't really celebrate, we were just exhausted. I lost all interest in the record business and never wanted to do anything except hand in a record again. To this day, I don't have any interest in it.

Q: "Long After Dark," which came out in 1982, coincided with the birth of MTV. How did the video channel change things for you?

A: In those days MTV was so hungry for product, you could have three or four videos an album. Suddenly, we had a lot of stuff on TV, and then your recognition factor goes up on the street. Instead of being on once a year, you're on all day long. People are seeing you all the time, so we tried to use it to our advantage, and it was so much fun.

By the time we'd done "Mary Jane's Last Dance," I remember thinking, "Can we line up stiffs in the video? Can we open on a line of corpses? Yeah! Sure we can."

Q: That segues perfectly into 1985's "Southern Accents." It is impossible to think of "Don't Come Around Here No More" without thinking of the video and "Alice in Wonderland." What was the band's response to the song?

A: Mike didn't like it, I think. The label hated it, [it] was like, "What the hell is this?" [laughs] It was one of the only times that I went, "OK, we're going to make a single." So it was a real satisfying thing to see it work. The video played a huge part in making it work, and it is a damn good video.

Q: What was the reaction to your cutting up Alice like a cake?

A: [MTV] actually made me edit out a scene of my face when we were cutting her up. They said it was just to lascivious. It was just a shot of me grinning, and they were like, "Well, you can do it, but you can't enjoy it that much."

Q: There may be some kids in Idaho who as a result of seeing that shot...

A: May see people as cakes.

Q: In the song "Southern Accents," you sing about your mom, who died in 1981. You did not go to her funeral because you thought it would cause too much commotion in Gainesville. That seems like a horrible price to pay for fame.

A: We knew it would cause a horrible commotion. My brother actually suggested that it probably wouldn't be a good idea, because even to this day, you know, my family, I go there, and they just get cuckoo. What we didn't want was for it to turn into an autograph fest and the Instamatics come out when it wasn't about that. I don't like funerals anyways. I don't think I missed anything by not going. I made my own peace with my mother.

Q: It is staggering how many people you have lost, from your mom and dad to people you have worked with like Roy Orbison, Del Shannon, Michael Kamen, George Harrison and Howie Epstein. Do you think that affects your writing?

A: Well, it could. I think it probably affects the way you live, you know. It makes you realize you really don't want to miss a day. George devastated me. I didn't think George could die. It so ripped my heart out that I still can't think about it. I remember when Roy Orbison died, I thought at the time if anybody had been prepared to go, it was him, because he was in such a good place mentally and spiritually. But then you see people who aren't ready to go. Howie, he wasn't ready to go. That makes you say a) I'm lucky to be here, and b) I better appreciate being here.

The biggest one, the one that bothers me the most, is my mother. She could have had everything she'd ever dreamt of and she didn't get to do it, and that one seems the worst to be because you just didn't get the payoff, you know.

Q: Thankfully, Bob Dylan survived his health crisis. In 1986, the Heartbreakers began a stint as his backing band. What do you remember about that time?

A: I knew we came away from that a better band than we went into it. In the rehearsals, Bob had a really extensive library of songs in his head: pop songs, folk songs, sea shanties. We opened in Tel Aviv with "Go Down Moses." We really got a confident feeling that "we can pull off whatever we've got to pull off here."

Q: Speaking of touring, you are coming off one of your top tours this year, and you seemed to be playing with such verve and zest. Were there times when it has not been fun for you to be onstage?

A: It's always been great to be onstage. In 30 years you go through periods that maybe you remember some more fondly than others, and maybe there's times when you feel more beat up than others. When Ron Blair came back, something clicked. Ron, without him even knowing it, brought something really needed back into the band. He clicked with [Steve] Ferrone in a way that Howie hadn't. It's really effortless up there. It's not a lot of work.

Q: You have always stressed that you really like being in a band as opposed to being a solo artist.

A: Oh, yeah. I probably wouldn't do it if I wasn't in the Heartbreakers. Not at this point in my life. Maybe it sounds egotistical, but they are one of the best rock'n'roll bands that ever played the music.

Q: While you were on break from touring with Dylan, an arsonist torched your house with you, your wife, and one of your daughters in it in 1987. How did that affect your outlook?

A: I think I came out of that not wanting to touch anything that was remotely angry. I think people who have been involved in some sort of violent act come out of it the same way, you know. I've seen it, where I can't watch that movie or I can't go there because I've seen the real thing and it's just not funny. So, when someone tries to kill you, you kind of have to re-evaluate everything, like, "What the hell did I do?" Then you think, "I didn't do anything, I just became a mark for someone."

Q: It seems that as a result of the fire, you did some of your lightest work.

A: Absolutely. I came so close to being dead, and I was just so happy that me and my family and everybody lived through that. I think I was a little giddy, just really happy.

Q: Shortly thereafter, you and Jeff Lynne started working on your first solo album, "Full Moon Fever." Is it true that you turned it in and MCA hated it?

A: It's the only time in my life thatr a record's been rejected. And I was stunned. And I was so high on the record, and I tried to think, "What did I do wrong?" They said they didn't hear any hits, and there turned out to be, like, four or give hits on the record, some of the biggest ones I ever had.

Q: Were you concerned that the album would be permanently shelved?

A: I just thought, "It's just stupid. I made this really good record and they don't want it." But I didn't, like, go to work on another one. I just joined the Wilburys, and this just sat on the back burner. That was actually when I signed to Warner Bros. We were at Mo Ostin's house, [and] the Wilburys played "Free Fallin'" that night. Lenny Waronker was there and said, "That's songs amazing," and I said, "Yeah, it just got refused at my label." Mo said, "I'll sign you up and put that out buddy. I'll sign you up right now," and I said, "You got a deal, Mo."

Q: But "Full Moon Fever" still came out on MCA.

A: We signed with Warner Bros. for when this deal ran out and just didn't say anything about it, but when a different bunch of bosses came in and they took the same record back and were like, "That's more like it, that's it, we'll put this out."

Q: So while you were in limbo with MCA over "Full Moon Fever," you went and worked on the Traveling Wilburys' first album, which came out in 1988. Were those two Wilbury albums as much fun to make as they seemed to be?

A: They absolutely were. That was really good, good place for me to be at that time in my life. I really kind of felt like friends took me in.

The nicest thing about the Wilburys for all of us was that not any one of us had to carry the load. I think it freed us all a great deal. George had wanted a band for a long time; he hated being a solo artist. It was George's dream. And I'm just glad it got to come true for him. We were proud being Wilburys and it was a lot of fun, but the greatest thing to me was there were some really long-lasting friendships made, and that's a kind of gift that you just don't get all the time.

Q: "Full Moon Fever" finally came out in 1989. Among the hits was "I Won't Back Down." If people did not already see you as a crusader, they sure did after a line like "You can stand me up at the gates of hell/But I won't back down."

A: Embarrassing.

Q: Really?

A: It was a little embarrassing. I thought, "Should I out this out?" It's so damn literal, there's nowhere to hide in this song. Jeff and Mike liked it. it was George Harrison that put it over the top. He played guitar and sang on it, and he took me aside and said, "This is really good, I really like this song." And then I thought, "Well, if all of them like it, then I'm going to put it out."

God, I could just be here all day talking about what it's done, the stories people tell me, how it's been applied to so many lives. That makes you realize that maybe sometimes it's right to say it and not to worry too much about metaphor.

Q: You keep your record and ticket prices down. You do not accept corporate sponsorships or let your songs be in commercials. Does it seem odd that some people consider you heroic when you are just doing what you think is right?

A: It's not heroic. Like you said, I'm just doing what seems right. I've never consciously done it. I'm certainly not a Robin Hood, I'm not that way. I just do what seems like the logical thing to do.

Like with the tickets, you know, it's been brought to out attention again and again and again: "You could be making twice the money you're making." We turn it down, I don't think with an eye toward being Robin Hood. I just think with an eye of, I want this trip to go on. I don't want to come through, burn everybody for $200 a ticket and then they can't afford to come see me again. Plus, I just don't think it's right. I don't think we need that much money.

Q: Why don't you let your songs be used in commercials?

A: Because I didn't write them to be orange juice commercials. Sometimes I feel like maybe it's a dumb move because I don't know if anyone cares, but I care immensely. I don't like it. I think it made [rock music] common and irrelevant. I think I'd get hives if I turned [the TV] on and saw my music playing behind the Gap. That would probably put me over the top.

Q: Your buddy Bob Dylan is doing it.

A: That's his business, you know. I have a lot of friends who do it. They're comfortable with it. That's fine if they see it that way. But I don't see it that way, so I just can't do it.

Q: And no tour sponsorships either. Same principle?

A: It's our band, you know. We started it from nothing and we own it, and I want people to trust it. It's not for sale.

Q: Can the band veto you?

A: Not really. I'm sure they know that if there's enough votes against me it will have a lot of power into what I decide, but I don't think they can veto me. I think think we've ever gotten to a "them-against-me" point. It's a democracy, but you gotta do it my way [laughs].

Q: You and the Heartbreakers came back together for "Into the Great Wide Open." The optimism continued from the solo and Wilbury work. It seemed like you had gone from being really angry to...

A: More observant, maybe. "Into the Great Wide Open" was the end of the 80s and into the '90s, and I was trying to deal, in a loose way, with some of that. The Gulf War had started. I think that played some small [part] in the record. In "Learning to Fly," stuff like "the sea may burn." I'm sure that came from the oil fires. I wanted that song to be a kind of redemptive song, only in the vaguest way, certainly not literally.

Q: Your last album for MCA was a greatest-hits package that included "Mary Jane's Last Dance." That was another classic video for you. What made you decide that Kim Basinger was a good choice for a corpse?

A: I said, "She's got to look really good, or why would he keep her around after she's dead?" I thought, "Kim Basinger would be good, I'd probably keep her a day or two, let's go see if she would do it." You can make a joke about it, but you do have to act a bit to be dead. It's not easy.

Q: In 1994, your second solo album, "Wildflowers," came out. There are some rock songs on there, but it is primarily dominated by gorgeous acoustic melodies.

A: That's my best one, I think, because I think it shows the whole scope of what I can do. "Wildflowers" covered really everything that had come into my brain and came out again. We drove the engineers so hard on that record, one or two snapped like twigs, and then there were some that couldn't make it. And I remember telling them at some really late hour, "Stick with me, kid, and I'll see you at the Grammys," and they did. Both [engineers] won a Grammy, and I was so proud of them.

Q: Rick Rubin, who produced "Wildflowers," brought you in to play on Johnny Cash's record. You must have been like a kid in the candy store.

A: I wasn't. That album, "Unchained," just blows my mind. I think it's some of the best playing the Heartbreakers ever did ... It would be on somebody else's record. But we really gave him everything we could give him. We would have died for him. I'm real proud of that record, even when I hear it in the commercials. [Sings] "I've been everywhere, man..."

Q: "She's the One" came out as the soundtrack to Ed Burns' movie of the same name. You scored the movie as well. Do you want to do more movie scores?

A: No, I think that cured me of ever wanting to do it. [laughs] I busted my ass on it, and then you see the movie and people are talking over it. I don't have time for that, I've got other stuff to do. I really liked Ed a lot and I thank him for giving me the shot, but it taught me that [that's] not where I want to live.

Q: You took "Free Girl Now" from the album "Echo" and gave it away as an MP3. Two days later it had been downloaded 182,000 times. This was in 1999 before downloading really took off.

A: It was funny, because Tony [Dimitriades] and I did that without really having the permission to do it. We just thought, "Try it and see what happens," but it went over bigger than we had planned. I think [the WB execs] were very nice, like, "That was funny, but don't do it again."

Q: It seems the relationship from Warner started to go south with 2002's "The Last DJ."

A: It was going south before that, because it was regime after regime coming through there. it was a very confused place at the time and, you know, I could feel that I don't have anyone here who understands me or who really understands what we're trying to do. At that point, the whole music industry had been turned on its side by the computer and by this sort of instant pop star that you can throw away and make another one. I don't know a lot about the music business, but I knew there was enough metaphor there to write a sort of moral play and use it as the vehicle. It was fun to sort of send them up and run them up the flagpole and have a laugh at them.

Q: A lot of people thought the title track was directed at Clear Channel, but it was not.

A: No, not at all. I thought Clear Channel put on concerts, I didn't know they had the radio thing. I knew it when they banned my record the first day ... Tony [told] me, and I was like, "Great, you can't pray for anything better than that." But the record got a bad reputation. I don't know if it's something I'd do again, but I'm kind of glad I did it.

Q: Do you think it did not do well because it was not what people expect from Tom Petty?

A: Well, too bad, you're going to have to take what he gives you. I don't give a damn what you want.

Q: Yes, you do. You have just spent hours talking about the respect you have for your audience.

A: Yes, well, that is respecting them. If I disrespected them, I would pander to them, but I don't. I never have, and I'm never going to. If you think I'm going to sing "Refugee" every time, I'm not going to do it. I'm too old for that now.

Q: What do you want to do?

A: I'm more interested in what I'm going to leave behind me now than in making a big hit record. I've refined what I do for a long time. If getting better at it means it goes over the heads of those who only wanted to party, then so be it.

Q: There is a great line in the song "Joe" on "The Last DJ" that says, "We could move more catalog if he'd only die quicker." So death really is a good career move.

A: Well, you always sell more. It's just a downright vicious song. It's black, black humor. I think I was hurt inside that you guys fucked this up, just the business in general, you fucked up this beautiful thing, this music that spoke for people. You turned it into this thing that nobody trusts, and it's, like, all for money. Like you weren't making enough money."

Q: What can we expect from your next solo album, "Highway Companion," when it comes out next year?

A: It has a lot to say about time and the passage of time. It's not so much love songs, it's not going to be what anybody expects from me, I'm sure of that. But it's good music, it's really good music.

Q: Do you see a day where you do not make music anymore?

A: My wife will tell you I'm not any happier anywhere than when I'm in the studio. I'm over the moon about it. It keeps me young, it keeps me feeling like I have some purpose. There's some reason this stuff is coming through me. So I don't intend to quit.

Q: Next year marks the 30th anniversary of the first Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers album. Are you surprised your run has lasted this long?

A: I specifically remember thinking if we had a five-year run, we'd look back on this and think that was a good run. Then it got to, "If we get 10 years out of this, it would be really something," so 30 years, incredible. I never thought we would do it this long. But you go back to '76, there weren't a lot of 50-year-old rock singers. Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley were the only people that I was aware of who had gotten old in rock'n'roll; everyone else had died or faded out. I just feel really pleased to be here.