Editor's Note: That last article is better read in the magazine itself.

Career Counselor: Play It Like Benmont

By Jon Regen

Keyboard - November 2009

In preparation for writing this issue's cover story, I had the enviable task of spending an afternoon in a New York City recording studio with Benmont Tench. Huddled beside a vintage Hammond A-100 organ and a Wurlitzer 200A, Benmont showed me some of his trademark fills and flourishes that have become such an integral part of the rock keyboard pantheon. He graciously let me into his tonal toolkit, showing me drawbar stops and piano parts to venerable hits like "Refugee," "Breakdown," and many more.

At one point while I was shooting video, Benmont launched himself into the ambidextrous piano and organ intro to Tom Petty's "Don't Do Me Like That." With the precision of a neurosurgeon, he comped the song's rhythmic piano parts on the Wurlitzer with his right hand, while effortlessly stating the tune's Hammond organ melody with his left. After finishing the intro, Benmont unassumingly interjected, "It's pretty dead simple stuff. You hear a texture, and you reach for whatever's up here, [points above the Wurlitzer], or whatever's up here [points above the Hammond organ]...."

Watching that video over and over again, it occurred to me that Benmont was absolutely right. It is a remarkably simple idea. You hear a sound, and find a way to execute it. Right hand, left hand, both feet -- whatever gets the job done. I never knew that Benmont played that timeless organ line with his left hand, but seeing him cover a virtual symphony of sound with his hands spread across two keyboards and organ drawbars (and his feet working both the expression and Leslie pedals) made me realize that often times, the solution to our musical problems is closer than we might think. We need only to listen to what a song needs, create that missing part, and play it any way necessary to make the music sing.

My time with Benmont lasted only a couple of hours. But the lessons he imparted to me will last a lifetime. Now, if I can only find a way to get that Hammond organ up four flights of stairs, I can really start practicing what he taught me.

More Than A Heartbreaker

By Jon Regen

Keyboard - November 2009

Benmont Tench on Playing with Tom Petty, the Power of Silence, and Listening to Everybody But Yourself

"F***ing play it! We're musicians. We're in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Play your f***ing guitars!" legendary keyboardist Benmont Tench cries out to his fellow bandmates in a scene from the recent four-hour, career-spanning Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers documentary Running Down A Dream. One visit to Tench's discography page at allmusic.com, and you'll quickly understand why he continually decries even the slightest scent of mediocrity, laying his musical, (as well as his verbal) heart on the line. In his nearly four-decade career, Tench has not only anchored Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers from their very inception, he's lent his soulful stew of Americana-meets-unabashed-rock-keyboard wizardry to countless albums by a few artists you just may have heard of: Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Johnny Cash, Aretha Franklin, U2, Don Henley, Roy Orbison, Neil Diamond, Joe Cocker, Warren Zevon, Randy Newman, Marc Cohn, Bonnie Raitt, Elvis Costello -- and the list goes on.

A longtime hero to both musicians and listeners alike, Tench's rare blend of raucous, rollicking piano and soaring Hammond organ has been a staple of rock music for over 30 years. Much more than just a founding Heartbreaker, he has long been music's secret keyboard weapon, injecting soul-drenched, scintillating parts into every session, song, and tour to which he lends his talents. Songs simply sound better because of Benmont Tench; imagine the Heartbreakers' classic "Refugee" without Benmont's blistering B-3 organ, and you'll begin to understand just how integral his playing is.

Tench is busier than ever these days, touring and recording with a wide array of gifted artists, including the WPA (featuring Toad The Wet Sprocket's Glen Phillips, and Sean and Sara Watkins of Nickel Creek), the Big Surprise Tour (with Justin Townes Earle, David Rawlings, Gillian Welch, the Old Crow Medicine Show, and the Felice Brothers), and countless others. As of publication, he's also prepping for the release of the long-waiting Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers Live Anthology box set, featuring rare performances of covers and Heartbreakers originals culled from the rock legend's archives.

Following a sold out stop on the Big Surprise Tour at New York's famed Beacon Theater, Tench and I sat down to talk about his search for music that matters, and his singular place in the pantheon of keyboard greats.

In an interview years ago, you said that painters and jazz musicians always strive to get better, and your sentiment was "Why shouldn't we?" -- that rock and pop music can sometimes become a haven for non-development. You seem to have been fighting that trend since the beginning.

Keith Richards said it, actually, about the Rolling Stones, when they came off their long hiatus, that he wanted to continue to grow it. And it's true. You know, I saw McCoy Tyner play three or four years ago. He's still going. Muddy Waters passed away at 67, Jerry Lee Lewis is still going -- he still plays even his hits with a lot of passion and fire. So I just don't want to ever stop trying to see what I can do that's different. Different and as good, or better, than what I've been playing.

People want to hear the hits, and if you go out on tour, you want to play what people want to hear. But you can't stagnate. I'm definitely a better musician than I was when I was 26, but I have to try to keep the mental freshness and naivete that I had then, and put something of what I've learned since.

The great fortune right now for me is that I'm playing with a lot of younger musicians who sing any genre of music. They understand, they strive, and they keep going, whether they're in theor 20s, 30s, or 40s. And it's really cool and encouraging.

What I think is really important, and something that Matisse and Bo Diddley had, is the idea that you're still young in the sense that you're still present. You're still spirited. Your best days are not behind you. This is still new and exciting to you.

So that's what you're still looking for these days -- that sense of adventure and growth?

Yeah. I want to play with people who are better than I am, or different than I am. And with the Heartbreakers, that's the case. I play with [guitarist] Mike Campbell and [bassist] Ron Blair all the bloody time. These are people that I learn from every time I play with them. And outside of that, Dave Rawlings, Gillian Welch, Jon Brion, Sean and Sara Watkins, Fiona Apple, who's remarkable -- these are people that just bring my heart alive, and that I listen to and I go blind, and I fall into that space where everything disappears.

It's true about jazz musicians. They keep going and going, and trying something new. And it's true about somebody like Elvis Costello. What I want to know is, can you do it in three-chord rock 'n' roll? In three-chord, old-time music? In real country music like they made in the '60s? Can you do it and keep it fresh? I want to hear that.

A lot of the time, the Heartbreakers managed to do that. Live. We've always been better live. But I think a lot of the time we've managed to throw in a Muddy Waters song. Or, on occasion, a Merle Haggard song or a Van Morrison cover like "Mystic Eyes." And even our old stuff, I think we still play it with presence.

The writer Barry Green quoted [bassist] John Clayton in The Masters of Music as saying, "When you're playing, listen to everybody but yourself, especially when you're soloing." If you can get to the point where you can do that. [Laughs.]

There was a PBS American Masters episode on author Garrison Keillor recently, and in it he said, "We see the world perfectly when we're children, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to remember what we saw." As you get older, it becomes harder to find that wonderment that was there when you were younger.

That's a really good term for it. The wonderment of it. The joy of it. That's what I'm looking for.

There were a lot of moments on your Big Surprise Tour show at the Beacon Theater that were like that. For nstance, I didn't know Justin Townes Earle, but when we sang "Mama's Eyes" I thought, "This is really the heart of what I'm talking about!"

That's the heart of what I'm talking about too, and I hadn't heard his record, but I had met him before when his did did a show or two with us. But with Justin, it doesn't sound like a studied thing, like "I'm doing revivalist country from the '50s." It sounds like, "Well, this is where my heart is." And that's what I always want to hear.

The best thing that Tom Petty does for me is he says, "Quit thinking about it. Do you want to rap about it, or do you want to play?" And that's really important, to keep yourself from over-thinking and over-intellectualizing.

It's really so much fun. I'm having such a good time. I'm playing with all these wonderful people, and discovering somebody like Justin. Everybody on that show was having such a good time.

One of the things that's so universally heralded about your playing is what you don't play. You're always serving the song, and letting the music breathe.

It's a couple of things. My father told me one day when I was maybe ten, just playing the piano, "You're playing too much." He said it kindly, and he was right. The Chuck Berry line, "I lose the beauty of the melody until it sounds just like a symphony" -- although I like symphonic music, I know what he meant. It's the same thing with Tom Petty and Mike Campbell saying "play less," and the fact that some of my favorite piano playing ever is on Beatles records. And I don't mean the solo on "In My Life," which is gorgeous. I mean that the piano comes in on the chorus of "No Reply" and plays those beautiful chords, all compressed, and then it's gone.

So you've always had an arranger's sense of "If I bring it in here, it means more when it goes away" -- that sense of thinking orchestrally within a song?

I think I just felt it that way. But also, I had really good people to learn from. The radio when I was a kid was the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Who, James Brown, Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, Tammy Wynette, George Jones, Frank Sinatra, the Zombies ... on and on.

Also, Tom and Mike, and [producers] Denny Cordell, Jimmy Iovine, and Rick Rubin -- I also learned a lot from them. Cordell said to [original Heartbreakers drummer] Stan Lynch, and I don't know the exact quote, bit it was something along the lines of, "Stanley, if you just don't play it, they'll always misinterpret you as tasteful." I think that's great, and it's true. So a lot of the time, I just don't know what the hell to play, and I decide not to play it.

I did a Saturday Night Live with Paul Simon 15 years ago. It was Paul Simon and Willie Nelson. And he hurt my feelings, but he was right. We were rehearsing a song, and he stopped the band and said, "What are you playing? That's meaningless."

Paul Simon said that to you?

Yeah. And you know, it stung, because I was still trying to figure out what to play. But he was right. You don't want to play something that's meaningless. I try to feel out what's missing, what would be good to have there, instead of just filling something up.

I was really impressed, aesthetically probably, but also groove-wise, by the kind of playing that Chris Stainton would do, where he would just play eighth-notes up high, all the way through "High Time We Went" by Joe Cocker. There's just eight-note playing in fifths, or something. So why do anything else? And it's also cool, like "Look how cool I am. I'm only playing eigths all the way through."

Simplicity seems to be a real hallmark of your organ and piano playing.

Well, it's ensemble playing. The Beatles were an ensemble. The Rolling Stones were an ensemble. And you listen to those records and things work against each other. I don't want to cover up what Mike's doing. I want to hear the way the guitars ring. And through working with the same band for a long time, and through them saying to me "Why don't you leave that out," or "Why don't you come in here," I learned so much. And I still do.

Also, I didn't play organ as a kid. I played Farfisa [organ] for a while, and then I switched to Wurlitzer [electric piano]. I didn't like the sound of Hammonds, I loved Matthew Fisher and Booker T. Jones, but I didn't like the "big Hammond with a lot of tremolo" sound. It seemed like it was trying too hard. So I didn't want to play Hammond.

In the Heartbreakers, I started playing a little bit of organ, partly, because, while I sang back then, and Stan sang all the time, my range was limited. So to fill in the parts where we would have liked to use voices, I started trying to play the organ as though it were background vocals.

That's amazing, because you're thought of as such an iconic B-3 organ player, but it really wasn't intentional from the start.

No, it wasn't. it wasn't at all. I shied away from it, because there were so many organists in Florida trying to play as well as Gregg Allman, and so many bands in Florida trying to be the Allman Brothers. The Allman Brothers were great, but there were so many poor imitations around, I think I came to associate the Hammond with bad imitations of Gregg. So it just turned me off.

So you initially came in playing Wurlitzer?

I played Farfisa the first time I played with Mudcrutch, and then I played Wurlitzer. I had a Wurlitzer with a Marshall stack. It was fantastic -- 100 Watts of a Wurlitzer. It got loud. We played some high school auditorium and cracked the ceiling.

Jonathan Cain from Journey spoke about he and Steve Perry intentionally tried to write songs that would stand the test of time. Similarly, your work in the Heartbreakers and other projects forms the soundtrack to many people's lives. I read reading your discography, and I kept saying, "Wow, he's on that record too." It's no small achievement.

I've lucked out. I've met people who like music that I like, and want me to play on their records. And I don't know how it happened. I've really been in the right place at the right time.

Benmont Tench's Live Rig

Keyboard - November 2009

"Benmont's had the same Hammond C-3 organ for 35 years," longtime keyboard tech Kevin Brown tells me. Brown, currently on tour with Phish, has been Tench's keyboard tech for 31 of these years, but has remarkably seen little change in the vintage-minded keyboardist's live rig during that time.

"Facing the audience, Benmont uses a Yamaha C7 grand piano with a Helpinstill humbucking pickup inside," says Brown. "Benmont actually had the first one of those, and he uses it along with an Earthworks piano microphone system as well." On top of the piano, Tench uses a Roland RS-5 synthesizer. "The Roland replaces the old Oberheims [pictured] that wouldn't stay in tune," Brown continues. "Benmont uses it mainly for string pads with a hold pedal, and brings the strings in and out with a volume pedal." Tench also uses a Roland PC-200 Mk. II MIDI controller to trigger samples from a vintage Akai sampler.

To the left of the piano is Tench's Hammond C-3 organ. "He uses it with a Leslie 147," Brown tells me, "and on top is a Wurlitzer Student Electric Piano, modified by [renowned keyboard restorer] Ken Rich." On the right-hand side of the piano is Tench's double-keyboard Farfisa organ. "On top is an original Yamaha DX7," Brown continues, "which he uses for the sitar sounds from 'Don't Come Around Here No More.'"

All Tench's keyboards run through a JBL full range speaker cabinet (used as a monitor), with an 18-inch driver and a 12-inch horn. The speakers are powered by Crown amplifiers, and the output runs through a mixer to the house.

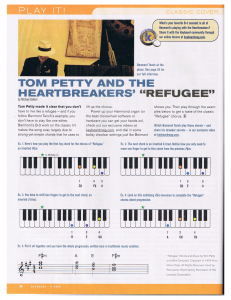

Play It! Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers' "Refugee"

By Michael Gallant

Keyboard - November 2009

Tom Petty made it clear that you don't have to live like a refugee -- and if you follow Benmont Tench's example, you don't have to play like one either. Benmont's B-3 work on the classic hit makes the song soar, largely due to strong-yet-simple chords that he uses to lift up the chorus.

Power up your Hammond organ (or the best clonewheel software or hardware you can get your hands on), check out our exclusive videos at keyboardmag.com, and dial in some ballsy drawbar settings just like Benmont shows you. Then play through the examples below to get a taste of the classic "Refugee" chorus.

Ex. 1. Here's how you play the first big chord for the chorus of "Refugee," an inverted F#m.

Ex. 2. The next chord is an inverted A triad. Notice how you only need to move one finger to get to this chord from the previous F#m.

Ex. 3. You have to shift two fingers to get to the next chord, an inverted E triad.

Ex. 4. Land on this satisfying F#m inversion to complete the "Refugee" chorus chord progression.

Ex. 5. Put it all together and you have the whole progression, written here in traditional music notation.