It's Good To Be King

By David Fricke

Rolling Stone #1093 - December 10, 2009

Tom Petty on growing up as a hippie in redneck Florida, the early days of the Heartbreakers and the stories behind his biggest hits.

"It's a strange thing to say out loud, but I felt destined to do this," Tom Petty says in a grainy baritone with a slow Dixie drawl. "From a very young age, I felt this was going to happen to me."

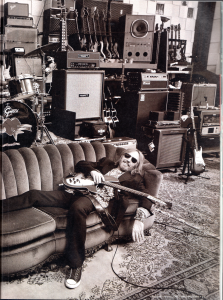

The singer-guitarist and leader of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers is sitting in the small lounge of a guesthouse at his home in Malibu, California, on a hilltop across the road from the Pacific Ocean. The walls are decorated with Heartbreakers concert posters and, near the front door, a framed charcoal drawing by Petty's friend Bob Dylan. Two rooms away, Petty has a fully rigged studio where he did a lot of work on The Live Anthology, a new multi-CD collection of concert performances by Petty and the Heartbreakers, drawn from three decades of roadwork.

"I was lucky: I have had a record deal since I was 23," Petty goes on, between sips of coffee. "It wasn't a lot of money, but it was enough to live. If I hadn't had a way to eat or a place to sleep, maybe I would have gone back." referring to his hometown, Gainesville, Florida, which he left for Los Angeles, and for good, in 1973. "But I wouldn't have quit trying."

The Live Anthology captures that ambition, and Petty's classic-rock roots, in full, with crackling versions of famous Petty songs like "Refugee" and "Breakdown" next to exuberant Bo Diddley, Them and Zombies covers. The set is also Petty's monument to the empathy and devotion of the Heartbreakers, especially guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboard player Benmont Tench, Gainesville natives who have been with Petty since the turn of the Seventies, when they were all in the hippie-garage combo Mudcrutch.

Despite its heft, The Live Anthology packs only part of Petty's extraordinary rock & roll life, which he reveals in intimate detail over two days of interviews at his home and at the Heartbreakers' rehearsal space, a warehouse in Los Angeles' San Fernando Valley. Petty, who turned 59 on October 20th, is as old as rock & roll itself and has intersected with its prime movers along the way, from his meeting, as a boy in 1961, with Elvis Presley (on the Florida set of Follow That Dream) to collaborations, in the Eighties and Nineties, with Bob Dylan, George Harrison and Johnny Cash, among others. Two of Petty's biggest-selling records are the 1988 and 1990 albums by the Traveling Wilburys, the casual supergroup he formed with Harrison, Dylan, Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne.

Petty knows he has been unique and lucky, to make music with his idols. "I'm glad I didn't make an ass of myself doing it," he says, laughing. Then he walks to the console in his studio and plays tracks from his next album with the Heartbreakers. They are recording in that warehouse, playing everything live with no overdubs, and Petty eagerly shows off the early results, including the electric-R&B charge of "Jefferson Jericho Blues" and "First Flash of Freedom," a psychedelic storm of steely jangle and biting-harmony guitars.

"I never saw another band where I went, 'Wow, I wish I could be in that band,'" Petty says firmly. "I always thought I was in the best band. And I still feel that way."

What have you learned about yourself as a songwriter from the new live box?

I was amazed at how durable the tunes were. I'm pretty rough on myself, as far as giving a pat on the back. I get nervous, to this day, bringing a song to the band. They're tough. It runs the gamut, from being very quiet, not saying anything. That drives me insane: "Well, what do you think?" Or Benmont can attack. On this new album, he broke bad on me one day. I was trying to show the band this song, basically a 12-bar song with a few changes. He went, "What the fuck? You're better than that!" He let me have it.

What songs have they loved -- or hated -- right away?

They all liked "Refugee" [on 1979's Damn the Torpedoes]. They liked "Spike" [on 1985's Southern Accents]. They didn't like anything on [Petty's 1989 solo album] Full Moon Fever -- "they" meaning everyone but Mike. I remember [bassist] Howie Epstein came to the sessions. I was playing "Free Fallin'," and he said, "I don't like that song." I said, "If you don't like it, you won't have to play on it." "OK, I won't. Bye." That wouldn't have worked as a Heartbreakers album. Benmont didn't like "I Won't Back Down" when he first heard it. And they didn't get [co-producer] Jeff Lynne.

But they're my brothers. It kind of landed in my lap, but they have been my family -- the only real family I've had. I look for their approval in the songs. When they give me "Good song," it makes my day.

How would you describe your style of leadership?

I know what the objective is, what we've gotta pull off, which is a lot of the game. Everyone tells me I'm a control freak. Maybe I am. Because I notice all the details. That was a characteristic I developed from having this huge responsibility on my back. If they weren't making enough money, they didn't go to Tony [Dimitriades. the band's longtime manager]. They came to me.

But I'm lucky, because they're so ridiculously good. They have a natural ability to make music, and I trust them so much. Like Mike -- there's never been a time when he wasn't giving me back more than I asked him to give me. He even engineered Full Moon Fever, because there was no one else there.

How have you changed? On a DVD in the deluxe edition of the live set, you sing "Fooled Again (I Don't Like It)" at a 1979 show. And you look pissed.

Maybe I was. I had an explosive side. It wasn't that easy to set me off. But when it happened, I lost it in a big way. I've learned to control that. But I had a tough childhood and took a lot of abuse. That rage was in me, and when it got away from me, I didn't know how to control it. But I could vent it in this music.

How tough was your childhood?

I had a wonderful mother. She was a very kind, good person. My father was Jerry Lee Lewis if he didn't play the piano. He was scary and violent. He beat the living hell out of me, and there was constant verbal abuse. Looking back on it, he probably was disappointed that I was so drawn to the arts. He probably thought I was gay. I wasn't interested in sports. I didn't know the names of any baseball players. I liked films and books and records. He liked to fish and hunt. He'd drag me on these trips, and it was a nightmare. Shooting something repelled me. My younger brother became a football player right away. He didn't want the same shit.

The music -- I was safe there. It was my thing. It rescued me in a big way.

How hard was it to be a longhaired rock & roller in Florida in the early and mid-Sixties? I hate to use the word "redneck"...

It's full of rednecks, no doubt about it. Gainesville is not Miami. It's not palm trees. It's just southern Georgia. There were a lot of bands there, because there were so many places to play: the fraternities, the clubs that catered to college kids, the teen dances. You had to be good. They would boot you out of the way if you weren't. My dad used to own a grocery store in the black part of town. He got out of that business, and that store became a black nightclub called Mom's Kitchen. They had terrific bands.

But I got my ass kicked a lot because of my hair -- threatened all the time. I remember driving on the interstate, pulling into truck stops. Our band would walk in, and the whole room would laugh. Some of them plain-ass wouldn't serve you: "You gotta leave." One time, our van broke down. We pushed it into a gas station, and they made us push it off, just because we looked the way we did. It made you see what black people were going through. It was nowhere as severe, but you sympathized right away.

You quit high school to go on the road, then went back to graduate. Why bother?

The shit I went through -- there were probably four or five guys in all of Gainesville with long hair in 1964. I got booted out of school so many times, told to get a haircut before I came back -- all that furor if your hair came down over your ears a bit or was kind of thick in the back.

It wasn't my choice to walk away from school. I was hanging around with guys older than me, and I'd skip school to play with them. I kept missing more and more school, and I got busted for it finally. But I went back. I felt like I'd be a real stooge if I didn't at least finish high school. I didn't want to be one of those guys who's just dumb.

What was the first big concert you saw?

The first concert I went to was in 1965. I was in this little band, the Sundowners, and the drummer's mom drove us to this show in Jacksonville, about 75 miles away. Let me give you the lineup -- it was incredible. The show opener with the Premiers, who did "Farmer John." Then Del Shannon came out and Lesley Gore, both backed by the Premiers. Then the Shangri-Las rolled out -- [singer] Mary Weiss was the sexiest blonde -- and Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs hit the stage with "Wooly Bully" and those turbans.

There was an intermission, and the Zombies came out and fried my brain. The singer, Colin Blunstone, had such an ethereal voice -- it was spooky. After them, it was the Searchers. They had those voices that sounded so good, and the 12-string guitar. Then the Beach Boys hit the stage -- all in one gig. I found out later that Mike Campbell was there. He worked in Jacksonville, and it was his first concert.

The Allman Brothers Band and Lynyrd Skynyrd were also from Florida. Why didn't you become a Southern-rock guy?

Gregg and Duane Allman were one of the first live bands I ever saw, when they were called the Escorts, doing Beatles songs and wearing collarless jackets. Later I went to a dance in St. Petersburg, when they were the Allman Brothers Band. The first album wasn't out yet. And it was just amazing. Lynyrd Skynyrd were on live shows with us, in the Mudcrutch days. I saw them more like a heavy English rock band.

We got reactionary to it. Everybody tried to be the Allman Brothers all of a sudden. We said, "We're gonna write shorter songs." We even went up to Macon, Georgia, to Capricorn Records, and brought a tape we'd made. They told us it was too English. That confirmed to me that we're gonna have to go to Los Angeles. Nobody here is gonna get it. The funny thing is, the album we're making now sounds like the Allman Brothers in some respects. It's blues-based, more jam-y music.

How would you describe the Heartbreakers' sound?

We're a garage band. And garage bands were a funny thing then, because you kind of played blues -- and didn't. You were playing blues in a way, because you were covering the Rolling Stones and the Animals. When we got older, we tracked down the names on their records, like Jimmy Reed. The Byrds and country music are part of that too, the big spectrum that got mixed into pop in the Sixties. We're good enough as musicians now that we can play all of that music without blushing. Without really trying, we learned a lot of different styles of music -- mostly from English people.

You and the Heartbreakers spent a couple of years, in the late Seventies, as a constant opening act. What was it like at the bottom of the bill every night?

We got thrown on whatever was going. I remember we were on the road with the Kinks, and the next thing we knew we were playing with Journey. We went from a few days of that playing with the J. Geils Band. Then, maybe the next gig, Edgar Winters was at the top, we're third, and J. Geils was in the middle. Sometimes we didn't know who we were playing with until we turned up. We got to this gig in Chicago -- it was a jazz club. We were on with Tom Scott and the L.A. Express. We walked out -- we had these Vox amps -- and somebody yelled, "What is this, the Monkees?" That did not go well.

One night with the Doobie Brothers, in Wheeling, West Virginia, was particularly bad. You had to take what you were given as far as stage room and monitors. I was so pissed. We played and went back to the hotel. I called a meeting and said, "We're never opening again. We're just going to play for whoever comes to see us."

That would have been about when I saw you in Delaware at a club in a trip mall.

That wasn't unusual. You had to work to win people over. It took us many trips to Kansas City and Chicago. We did a show with Elvis Costello very early on. We still laugh about it when we get together. It was Elvis Costello and the Attractions, and us, in a 1,200-seat theater for a buck. And we didn't sell out.

In a sense, you had one of the last great rock & roll upbringings. "The Last DJ" [2002] is your elegy to an era you knew firsthand and most people now can only imagine.

That's something I think about a lot. For so much of my life, I took rock & roll seriously. I wonder if people understand how much that meant. It was a renaissance period -- artists were doing their great work. But you took it for granted that it was just going to go on and on. It was sad to see rock & roll shoot itself in the foot.

When did that happen? Do you have a specific date?

It's all about greed. When people realized there were fortunes to be made with this stuff, it changed. Let's go to radio. Playlists narrowed to only sure things, which inhibited creativity. I remember being stunned, in the mid-Eighties. I had done some song that I thought was fantastic, and the record company told me, "They only want fast songs with a guitar break in the middle." I was speechless: "Oh, it doesn't matter what I do."

You probably had a fast song with a guitar break all ready to go.

Yeah. But it wasn't what I thought was the best song. And MTV -- I could tell right away that was going ro rule out anybody not clever enough to make a video and look good doing it. I adapted. But the audience started to change -- I saw people being fed shit and only too happy to eat it.

Let's talk about some hits. Was there a real-life "American Girl"?

There's not a specific girl. I wrote it very quickly. I was living in an apartment [in Los Angeles], and there was a freeway behind it. The first bit of lyric came with these cars going by -- it sounded like waves crashing on the beach. I tied that up with Route 441, which was the main drag through Gainesville ["Yeah, she could hear the cars roll by/Out on 441 like waves crashin' on the beach"]. I was creating a girl like I knew in Gainesville, the kind who knows there's more out there than the cards she's drawn.

Which comes first, words or music?

I've written songs in all kinds of ways, but the best ones are where you get some lyric and melody at the same time. "American Girl" -- I'm sure that as I was doing the chords, the words fell into place. "Even the Losers" [on 1979's Damn the Torpedoes] is an amazing story. I had written all of it but the chorus. Every time I got there, I drew a blank. This is how bold I was. I said, "Let's cut the song; I'll get those words later." On the first run-through, those were the words that came out: "Even the losers/Get lucky sometime." It fell out of my mouth, a perfect example of working backward to get to the right thing.

"I Won't Back Down," on "Full Moon Fever," is more like a mantra than a song.

That put me off when I wrote it. It's so bare, without any ambiguity. There was nothing there but truth. There was another issue going on, though. Someone had tried to kill me, with the arson at my house. [In 1987, someone set fire to Petty's home in Encino, California.] I took that personally. Surviving something like that makes you feel alive.

That was my mind-set: I will survive, I will move on. It blurted out of my mouth. I changed one thing. There was a line I was singing, "I'm standing on the edge of the world." When we cut the record, George Harrison was there. He played and sang on that track. And he goes, "Tom, what the fuck is it with 'standing on the edge of the world'?" I was like, "Oh, busted."

By a Beatle, too.

I went, "Yeah, you're right. That doesn't mean anything." I thought for a minute and went, "How about, 'There ain't no easy way out?'" George went, "Much better."

You have worked with and been personally close to legends such as Harrison, Dylan and Johnny Cash. Why do you get along so well with your elders?

The odd thing is, I never sought any of those people out. Every one of them came to me. Obviously, they liked something we did. At times, I think they were looking for some help, like "I need to put a band together." We had this unit. Bob used to say, "These guys communicate without talking." He liked that.

One thing I had in common with them was when I was 10 or 11, I got into the music of the Fifties. I knew it inside and out. When George and I met, that was our common ground. I knew that Gene Vincent album. We would sit and play that stuff. With George, I think his interest in rock waned around 1962 [laughs].

You and the Heartbreakers toured as Dylan's backing band for two years. What did you learn from that experience?

He had a good way of showing us what he wanted with his guitar. He'd say, "It's this kind of rhythm, and here's how the chords go," and everybody would fall in. We might play it for five or 10 minutes, until it took the right shape and he said, "That's the way to do it." He's an encyclopedia of songs. For the Farm Aid show [in 1985], we rehearsed a lot of his songs and a lot of covers. It wasn't a long spot in the show, but we rehearsed so much stuff. We did Smokey Robinson's "The Tears of a Clown." I remember we did "Come Together," by the Beatles. It sounded great. But we never played 'em in the show. It was like, one day, we'd play these songs. And then they'd never come up again.

You hooked up with Dylan as he was coming out of his Christian period and about to start the so-called Never Ending Tour. Could you see any changes?

In his book [Chronicles, Volume 1], he says he was going through a hard time: "Tom was at the top of his game, and I was at the bottom of mine." I didn't know he was so conflicted. It's hard to speak for Bob. But I remember the night he talks about in his book, about going up to the mike to sing and nothing came out of his throat [October 5th, 1987, in Locarno, Switzerland]. He took a breath, started again, and it worked. He had some epiphany about staying on the road. I remember that, because I was scared for him: "Uh-oh, something's wrong." Then he sang, and I didn't think about it anymore. It's funny what goes on in people's heads onstage. You don't know. You're just communicating through music.

Harrison was away from music for long periods of time. Did having someone like you around help him feel engaged?

I had the feeling he was always dying to play. When he came over, you were gonna play music for an hour or two. He was very up, very active. One time, he came over, and I was sick. I was in bed -- "Man, I don't know if I can party tonight." He came in the door, right up the stars, and sat down on my bed: "C'mon, you're not that sick. Get up."

Did Harrison talk about touring, especially after the first Wilburys album was a hit?

A part of him wanted to do that. That would come up, usually when we were a bit happy [smiles]. Then the next day, it was gone. He couldn't come to terms with it. At one point, he said, "We should get a ship, just sail around. We could pull into a cove and play to guys in outrigger canoes. And we'll call it the Sponsor Ship. We'll paint a different corporate logo on it every day. That'll pay for the trip." He was so funny.

His biggest problem was the machinery of managers and booking agents. He said to me once, "I can't face waking up in Philadelphia and having to go to the soundcheck."

You played in a partial Beatles reunion. Harrison and Ringo Starr appeared in your video for "I Won't Back Down."

It was George's idea to get Ringo. What am I going to say -- No? I knew Ringo. He would hang around with us. But I still can't believe that happened. We had amps on the set, and we'd be jamming between takes. I remember playing and looking at Mike, like, "How about this?"

What new artists excite you?

The latest new record I like is Monsters of Folk. There are some fresh things there -- good, solid songs and singing. Regina Spektor is great. She has such a clear voice, and the songs are smart and soulful. I don't think it's ever a case of there's nothing good. It's just getting harder and harder to find it. It used to be that to make an album, you had to do something pretty well. To get to make a 12-inch record -- that was an honor. Now everybody does it. You go to a restaurant, and the guy playing in the corner has an album.

How is your commitment now?

I don't know what kind of future we have. I can't imagine starting out in this atmosphere. What it's done to me is given me a great liberation. I feel like I can do whatever I want. This live album -- I spent a lot of time sequencing the tracks, making them into shows, where each disc presents a whole program.

You could take the point of view "It's gonna hit iTunes, 80 songs, andn people are just gonna pull what they want." But there's somebody out there who will sit down and take it as the work it is. So I have to keep doing that. If I didn't, I would be a sham.

You also run the risk, on an album like "The Last DJ," of sounding like one of those grumpy guys who says, "It was better then. They don't make rock like they used to."

I don't think I'm a bitter old man. I'm an optimist. I believe in the human spirit. I believe we can overcome a lot of things. But it gets harder and harder, with the way things are.

I'd love to say, "Shit is so much better now" [laughs]. But it was better then.

In the Great Wide Open

Review by Mark Kemp

Rolling Stone #1093 -- December 10, 2009

A new box set captures the freewheeling power of the Heartbreakers live

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers | The Live Anthology | Reprise | ★★★★½

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers' only previous live album, 1986's Pack Up the Plantation, was a stone bone: The note-for-note versions of "Refugee" and "American Girl" didn't come close to capturing the excitement of a Petty show. The Live Anthology redresses the wrong with a panoramic picture of the Heartbreakers' indestructible groove. Powerhouse versions of "Even the Losers" and "Here Comes My Girl" -- stretching from as far back as 1980 -- show off the band's muscular snap. Guitarist Mike Campbell chimes his way through "The Waiting," gives a Keith Richards twang to "Louisiana Rain," and with keyboardist Benmont Tench helps prop up weaker songs like "My Life/Your World." But it's the covers that make this four-disc collection interesting to more than Petty completists: The Grateful Dead's "Friend of the Devil" gets a down-home charge; "Diddy Wah Diddy" is a slinky winner; grooving instrumentals like Booker T. and the MG's "Green Onions" and the James Bond Goldfinger theme (from a 1997 Fillmore show) display the band's range; and a hungry take on Fleetwood Mac's blues-era "Oh Well" (from the 2006 Bonnaroo festival) shows the Heartbreakers' roots. And if you are a Petty completist, you'll have a wealth of choices: The collection comes in four other configurations, including a massive deluxe edition, which adds a fifth disc of music, two DVDs (a documentary and late-Seventies concert) and other fanboy bonuses.

Key Tracks: "Refugee," "Melinda," "Diddy Wah Diddy"