The Mojo Interview

By Mat Snow

Mojo - January 2010

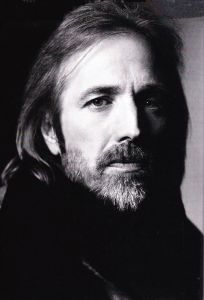

The bard of blue collar rock has led the Heartbreakers to glory and on through tragedy. "Wounded" on the way, he has endured "abuse" and "rage." "I slowly found my way back," reveals Tom Petty.

Tom Petty is sitting at the wheel of a crimson Cadillac parked outside his guitar-lined warehouse den-cum-studio in Los Angeles' shabby Van Nuys district as the rain pelts down, and the man is rocking. Three tracks from his current album-in-progress with his band the Heartbreakers are blasting from the stereo, and the nervy quiver of a man fuelled on black coffee refills and king-size Shepheard's Hotel cigarettes vanishes as he air-guitars, hair-shakes and pumps a denimed leg, entirely lost in music—his own.

And who can blame him? We're here to mark the past in the hefty shape of the multi-CD/DVD Live Anthology package documenting three decades of Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers delivering on-stage time and again despite traumas—many self-administered—that would have finished most other bands years ago. But actually, as Petty enters his 60th year, he's really, really excited about the future.

It's a future he found by reversing down a detour. Two years ago, he took a sentimental journey with fellow Heartbreakers Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench when, for one album and a few live dates, they reformed Mudcrutch, the band they'd formed in their native Gainesville, Florida, hoping to break into the big time in the early '70s. But they split by order of the record company, to Petty's lasting guilt. In the spirit of the original Mudcrutch, the glued-together outfit would be a band of equals: no leaders, no egos.

For Petty, the results and the pleasure he got from the process were both a revelation and a roadmap: "I'm writing for the band. I don't come in with the demo like I did with The Last DJ [the band's controversial 2002 album; see sidebar on p44] with it all mapped out. Now I come in with a skeleton, a framework, which I play to them on the guitar or piano. And voila! They play it and we try to capture it live. There's a purity like in the old blues record which I like at this point in my life. I'm so lucky to have this incredible band that it seems a shame to tell them what to play. I want to trust the chemistry of the musicians; I want music to be people playing."

And play they do. Think Allmans meet Dead meet Led Zep meet Dylan '65 meets, well, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers. as a fan and DJ on his radio show Buried Treasure, Petty is rooted in the past, his fave raves right now being Ann Peebles, Mose Allison and The Who's first album. But as a musician, and in part thanks to no longer having to write a hit single to carry an album since there are no meaningful hit singles any more, his eyes are on a new horizon: a band of musicians playing their way into a whole greater than the sum of its parts. To reach this plateau of musical and human wisdom has not been easy. As he reveals over two hours, the path has been strewn with obstacles and demons from the very start...

Your mother was a clerk in the tax office, your father a man of many occupations and mistresses. What characteristics do you think you inherited from each of them?

My father was a very charismatic guy, like Jerry Lee Lewis with no talent. He was a very good story-teller, and maybe I inherited some of his ability. But I wasn't his hunting or fishing buddy, and he was very hard on me, very abusive. But in some ways he was a fair and honest guy; I never saw him rip anybody off. I hope I've inherited the best of him and not the worst. My mom was a very sweet, gentle soul, a very calm, kind person. We were from country people, and my mom aspired to be a city person and become a little more sophisticated. She encouraged my interest in the arts, bringing me books and record, and would pay for me to go to the movies. My dad couldn't see the sense in that; I don't think he ever went to the movies.

You were of a generation inspired to form a group by the British Invasion. Then, in 1970, your band The Epics morphed into Mudcrutch. But you didn't follow local heroes the Allman Brothers Band into Southern rock.

You couldn't throw a rock without hitting some band trying to imitate that style. I was put off by that; I loved the real thing but wasn't at all interested in the imitators, so we stuck to what we were doing and had become as successful as we could without being signed. There was nowhere else left for us to go except around the rink again. In the South, songs were going away, and I wanted to be a songwriter in a song band. It was inevitable we'd go to California; I loved The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, The Beach Boys.

Were you still good ol' boys?

We came from that but we weren't rednecks (laughs). We were exposed to brighter things. I was never a racist, and my friends certainly weren't, but you could see that element in a lot of people down there and it wasn't pretty. We liked to think of ourselves as a little hipper than what was going on.

Mudcrutch split when label boss Denny Cordell decided only you had star potential. When you reunited with Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench, Cordell's contract required you to lead the band—hence Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers. Did being main vocalist, songwriter and stage focus affect you?

I had to become all that. I'd been the bass-player and one of the singers, not the only singer. I tended to sing the Bob Dylan and Byrds stuff, because that's what I did well. I had to switch to guitar, which I'd never played on-stage, and I had to learn to entertain the crowd, which I was still getting together when I first came over to England [in 1976].

You married at 24. Was there room for women and relationships in the band of brothers and the adventure you were having?

Not as much as there should have been. We'd all learned to survive with girlfriends. In those days band girlfriends had apartments or some sort of support system, so became very popular. But it was a constant struggle between having a normal life and living with your brothers.

We all lived in one house, haha. It had to be very hard for the girls. I was very naïve thinking I could pull it off. Musicians do tend to marry very young; it's odd if you don't need the support if someone there waiting for you, but it's not a great idea. My kids tell me the same thing as an open joke: my music and the band meant so much to me that they might have come in second. It's not an easy profession to grow up in; it doesn't encourage growing up at all (laughs).

Roger McGuinn joked that your second single, 1977's American Girl, was a Byrds song he'd forgotten. Were you finding your style by working through those of your heroes?

American Girl doesn't really sound like The Byrds; it evokes The Byrds. People are usually influenced by more than one thing, so your music becomes a mixture. There's nothing really new, but always new ways to combine things. We tried to play as good as whoever we admired but we never could.

Was American Girl based on someone in particular?

No. She was a composite, a character who yearned for more than life had dealt her.

Is she the same girl 10 or so years later you treat so badly in Free Fallin'?

Maybe. I return to that character a lot. Mary Jane's Last Dance is the same girl with a few more hard knocks.

Do your songs reflect your upbringing by defying masculine bullying and sympathising with women suffering hard knocks?

My dad tended to roll in after I was in bed. I was always surrounded by women. As a child I lived with my mom and grandmother. My mother's two sisters were around a lot, and one of them was divorced. So the ladies were the family and I've always liked them and never felt any disrespect for women and could always get along with girls. Writing songs, I felt women's trials and tribulations because I saw a lot of it and I sympathised. I don't think I was aware I was doing it, but it's there in hindsight.

Your mother died when you were about 30. Did that make you angrier because your father was the survivor?

I'd really lost my mother years before. She had a brain tumour which she fought for years with chemotherapy. She developed epilepsy and couldn't talk. From the time I was 20, there was no mom, really. I hated my dad. There was one time he showed up with a young girl at the band house. I was really furious, really mad, that he would come to my friends' house and make me hang with him. Now I can understand that he was going through a terrible time and didn't know where to turn. He was quite ill himself in the latter part of life.

Forgiveness is the key. You have to forgive people and try to understand. That's easy to say and a lot of work to do (laughs).

Mixing Southern Accents in 1985, you got so frustrated you broke your left hand punching a wall. That's a lot of frustration to jeopardise your playing ability, and your career, in such an outburst. Was it just a bad day or did you have, as they say, anger management issues?

Both. I've really worked to get that under control and I'm much better with my temper which I'm sure is a direct result of my childhood. I've always had a huge capability for rage. When I felt any sort of injustice had been done to me, I could just erupt into absolute rage. That comes from being an abused child. It took a lot of work but I feel it's out of my system now.

I went through many years of therapy staring in the '90s and I wish I'd gone sooner. I didn't understand what I'd been through because it was all I'd ever known. I had to learn that spazzing out completely, just going insane, only furthers the problem.

In Peter Bogdanovich's band documentary, Runnin' Down A Dream, you admit you lured Howie Epstein from Del Shannon's touring band to replace bassist Ron Blair in the Heartbreakers despite Del's appeal to you not to. You can be ruthless, can't you?

I can be ruthless when I'm going after what I want (laughs). And I wanted him. And he wanted to be with us. I really loved Del but I so wanted Howie and I knew there was more future with us than he had with Del. It was a no-brainer. It's the thing with women: Look, that's the one I want, and there's nothing I can do about it.

Have you done that? Taken someone's wife or girlfriend?

Well, I've tried not to. But, you know, you gotta do what you gotta do...

Among your non-Heartbreakers co-credits are your hit Jammin' Me and songs for The Traveling Wilburys. So how do you write a song with Bob Dylan?

There's nobody I've ever met who knows more about the craft of how to put a song together than he does. I learned so much from just watching him work. He has an artist's mind and can find in a line the key word and think how to embellish it to bring the line out. I had never written more words than I needed, but he tended to write lots and lots of verses, then he'll say, this verse is better than that, or this line. Slowly this great picture emerges. He was very good in The Traveling Wilburys; when somebody had a line, he could make it a lot better in big ways.

Bob Dylan, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, George Harrison and you: in a band of bandleaders, who was the alpha Wilbury?

Definitely George. It was his idea, his vision. The band formed around a George song. We thought initially we were making an extra track for George, but he listened to it and said, "This isn't a George Harrison record; let's form a band."

So among all these bandleaders, it was the former third fiddle in a foursome who runs the show!

Yeah, he'd only ever been in one band. But he was the best bandleader I ever saw. He was really good at organising things, at knowing who was best at what, delegating what to do. And he was a great record producer and made the process a lot of fun; he instinctively knew when the session's bogging down and it's better to forget that problem and go onto another one and keep the energy going. That's a lot of what a good producer knows how to do: keep the session on an up.

Did your 1989 solo debut album Full Moon Fever, quickly recorded with Jeff Lynne, upset the Heartbreakers?

They were really pissed. This is a bunch of people who've been running around together since we were kids—a lot of baggage. I think their biggest fear was that I was leaving, 'cos after that I joined The Traveling Wilburys. I wasn't, but I'd been on the road with them for two years straight and needed a break. I was toast.

The idea was to make a solo record—I had things I wanted to do without going through the political process of the Heartbreakers, though Mike played on it quite a bit, Howie sung one background part, and Benmont played a piano fade-out. Benmont was very angry; he came in, played and walked out after one take—never said a word, not hello or goodbye. Especially Stan [Lynch, drummer] was really burned about it. As a peace offering, I did a song with them, Traveling, which I wrote driving to the session. At the end they were all pissed off—didn't like this, didn't like that. So I didn't go back again. Fuck it. You can't even get along for a day. When we started playing again, Mike and Ben were fine. But Stan never got over it, and because it was such a huge hit, he was doubly insulted.

What came to a head with Stan in 1994?

Stan had lost all allegiance to us and was auditioning with other bands. I had the feeling he was only staying around for the money. Neil Young's Bridge School Benefit in San Francisco was the last time we played together. The Heartbreakers very rarely have a terrible gig, but the first night of those shows there was a bad vibe on the stage and we were terrible. In the van going back we had a big argument. The next day we did another show and by then Stan had pissed everyone off. It was irreparable; the marriage had ended.

Your manager Tony Dimitriades gave Stan the hard word. Were you too angry to tell him?

I was too chicken. I was a coward! (laughs) I did have a long talk with him before about him leaving the band, so those cards were certainly on the table, and at the end of the conversation we agreed we'd each think about it overnight. But then it was, "Tony, you're going to have to tell him—I just can't face him."

Was your retreat to a shack in the woods in 1995 a midlife crisis or something else?

I just was not happy. I needed more than a hit album in my life. I needed to feel good about myself. And I was in an unhappy marriage. Musicians can stay on the road for five years and not deal with your marria,ge, (laughs), but it came to a point when I was going to face these demons. I got divorced. I'd hit the wall.

Oddly, it was in a period of great success musically. But I had to retreat and live completely alone. I didn't go out, didn't do anything but sit in the house most of the time. I was just wounded and crawled off to lick my wounds.

What did your kids make of this?

They were very upset. It was very hard on my family. It was around the time I went into therapy and I slowly found my way back, little by little. And when I finally made the transition, I was much better for it. But it was a very rough time, the darkest period of my life.

Ben Tench has spoken of cocaine use, there have been hints that to an extent you were all substance fuelled. Did drugs work for you?

No. They finally killed one of us. Drugs don't work. I'm not one to tell people how to live, but I've never seen it work out for anybody. You never see somebody and say, "The cocaine is really looking good on you." Musicians have always been drawn to drugs, especially marijuana and heroin, because they're probably the most musical drugs—they enhance music. Coke is the most useless drug I ever came across because it don't do nothing but make you want more coke, and irritable and edgy. I never thought it was good for music. Marijuana is very musical. But nowadays it's not like the stuff we used to smoke and make records with. Nowadays, if I'm going to smoke pot, I would do it at the end of the session when we're playing stuff back. Otherwise it would slow me down. When you're writing sometimes it can open a creative door. But it's a falsehood that it's an automatic ticket to better music; that's just not true. And now, with drugs, I would feel dumb ODing and dying; I would feel it's a joke death. You know better than that. And after Howie I could never think about doing...that.

In hindsight, was Howie Epstein—who died in 2003—always vulnerable to depression and substance abuse?

He was a tough little guy. He was a gentle soul, very kind and nice and sweet. He was the one Heartbreaker who never seemed jealous or envious or catty about anything; you always knew right where you stood with him. And then he had this side of him... Howie had friends, who'd show up who were serious bikers, Hell's Angels-types. And he'd carry a gun sometimes; I thought that was odd.

Might those two things connect to the fact that he was using heroin?

We knew he was using, for a long time. It did eventually affect his gig, but for the longest time it didn't seem a real problem. Howie didn't have around him the best people, somebody that he really listened to. He certainly didn't really listen to me. I didn't have that power with him, and I don't think any of us did. (Sighs deepy) God, he was a very talented guy. He made that record with John Prine, The Missing Years, and Carlene [Carter]'s record after that [Little Love Letters], going so well and as happy as he could be. I thought that he'd found his feet, and then the drugs just got worse and worse. That doesn't happen when someone's not in serious pain. But on the surface his life was pretty good. He never talked to me about his childhood or what he'd been through. His parents were both gone and he didn't have any family around him.

How did it end?

We'd had some really awkward incidents on the road and we had it worked out for him to go straight to a rehab on an island that we knew about. On the last night of the tour we were flying back to LA and there was going to be a car which we'd put Howie in to take him away. But near the end of the flight he came up to me and said, "I'll go tomorrow because I've got to go home." I said, "I don't think that's a good idea." He said, "I've got to go home—I haven't seen Carlene in a long time." I said, "Look, you're going to make me look like an asshole if you don't go." Of course, he never went. He went home and (sighs) that was that.

Of your many songs, the creation of which ones hold the most resonant memories?

I Won't Back Down—so many people tell me it meant something in their lives. At the session George Harrison sang and played guitar. I had a terrible cold that day, and George sent to the store and bought a ginger root, boiled it and had me stick my head in the pot to get the ginger steam to open my sinuses, and then I ran in and did the take. I put my heart and soul into those records. I remember things about making them pretty vividly. It's a great job to have. The best thing to do with your life, I always tell young people, is to try and figure out what you like and make it your work. I'm incredibly fortunate in that respect. I knew when I was very young that I was going to do this job. I didn't do it to make money. I thought I was giving up the chance to make money—musicians who are constantly employed are very few. But I was sure I'd make enough to get by and be happy doing it. Now you see people wanting to start at the top, like on American Idol.

Would you go on American Idol to show them how it's done?

Noooo! I never see guitars on that show (laughs).

We're Not WORTHY

The "cool music" mixer by Julian Casablancas

"It's not one thing with Tom Petty, it's a mixture of everything, his singing, songwriting, the music, how it's played, the mood he creates is perfect. If you mix all the cool colours together you get this brown; he's like when you mix all the cool music together it's not bland. His music evokes the best feeling. It's honest, subtle and happy."

Tom's TRAUMAS!

Petty vs The Rest in three top albums. As told to Mat Snow.

Tom vs. the Man

Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers | Hard Promises | ★★★★ | Backstreet, 1981

After 1979's breakthrough hit Damn the Torpedoes, the record company tried to hike the price by a dollar. "I was really insulted they were going to use me as a guinea pig to raise the price of albums across the board. They told me to go home and mind my own business. Not a single aritst backed me up, but I was right. Part of the destruction of the record business was over-pricing."

Tom vs. the Band

Tom Petty | Full Moon Fever | ★★★★ | MCA, 1989

"Jeff [Lynne] and I hit it off right away, and we had a ball hanging out and working. The music was written and recorded really fast; I made that album in about 10 days, stopped, then three or four months later did a couple more tracks. Full Moon Fever put some severe wounds into the Heartbreakers. In that respect, it wasn't a good thing to do but some really good music came out of it."

Tom vs. the 21st Century

Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers | The Last DJ | ★★★★ | Warner Bros, 2002

"Radio was just a metaphor. The Last DJ was really about losing our moral compass, our moral centre. We don't care who gets hurt any more in the quest for the dolar. That was what it was trying to say. My mistake was hanging so much of it on the music business: where had I been, under a rock?"