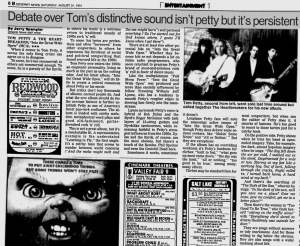

Debate over Tom's distinctive sound isn't petty but it's persistent

By Jerry Spangler

The Deseret News - Saturday, August 31, 1991

TOM PETTY & THE HEARTBREAKERS; "Into the Great Wide Open" (MCA) ★★★

When it comes to Tom Petty, it seems the only thing critics can agree on is to disagree.

To some, he's too commercial; to others not commercial enough. To some, he is a parody of the Byrds; to others his music is a welcome return to the traditional sounds of 1960s rock 'n' roll.

To some, his lyrics are pretentious and often "borrowed" from other songwriters; to others he represents the forefront of social and political songwriter that found renewed life in the 1980s.

Tom Petty now enters the 1990s an enigmatic personality, living as much in the past as on the cutting edge. On his latest album, "Into the Great Wide Open," will do little to create a critical consensus about Petty or his music.

But critics don't buy thousands of albums; normal people do. And what the new album should do for the average listener is further establish Petty as one of America's finest pop-rock craftsmen. The album is loaded with catchy melodies, metaphorical word plays and good old-fashioned, guitar-drenched rock 'n' roll.

This is not a great album, but it's a comfortable fit. A representative example is the understated "Learning to Fly," the first single. It's a catchy tune that seems to wander between world concerns ("And the rocks might melt and the sea might burn") and personal searching ("So I've started out for God knows where, I guess I'll know when I get there").

There are at least five other potential hits on 'Into the Great Wide Open." Whether they become hits or not depends a lot on fickle radio programmers, who seem reluctant to program Petty's brand of meat-and-potatoes rock 'n' roll in favor of dance music.

Like the multiplatinum "Full Moon Fever," "Into the Great Wide Open" was produced and more than casually influenced by fellow Traveling Wilbury Jeff Lynne, who has a tendency to smooth Petty's rougher edges in steering him firmly into the mainstream.

Lynne surrounds Petty's voice (a hybrid of Bob Dylan and the Byrd's Roger McGuinn) with lush layers of 12-string guitars and Byrdslike tambourines, while remaining faithful to Petty's strongest influences from the 1960s. Dylan and the Byrds, of course, are the most obvious, but there's a touch of the Beatles, Phil Spector, and even the Grateful Dead here.

Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't.

Longtime Petty fans will note the somewhat softer tempo of "Into the Great Wide Open," though Petty does deliver some serious rockers, like "Makin' Some Noise" and "All or Nothin'." But they are exceptions.

If the album has an overriding weakness it's Petty's fondness for cliches: "built to last," "what goes up must come down," "the sky was the limit," "all or nothing," "too good to be true," among many, many others.

Cliches may be standard fare for most songwriters, but when one the caliber of Petty goes it, it smacks of laziness. He's too good to resort to those tactics just for a catchy hook.

On the positive side, Petty shines when he tries his hand at open-ended imagery. Take, for example, the dark, almost hopeless imagery when he sings: "The day fell down the air got cold, I walked out in the street, Daydreamed for a mile or two, Staring at my feet like a working boy, Out of luck, falling through the cracks, Night rolled in, I turned back home, A hard wind at my back."

And there's the searching of "The Dark of the Sun," wherein he sings: "In the dark of the sun, will you save me a place? Give me hope, give me comfort, get me to a better place?"

Then there's the woman in "Too Good To Be True," who finds herself "sitting in the traffic alone" with "Everything she'd dared to dream/Suddenly was outside her door."

They are songs without answers or tidy conclusions. And for those willing to dig below the obvious, they are also songs with a wider meaning about life.